A Carry Adventure through Portugal and its Heritage Artisan Leather Industry Part 1.

In the worst of the dirge and the frost of a long, bleak Berlin winter, Portugal was the vapour-lined mirage on the horizon of my vitamin-D deficient, landlocked mind. I kept hearing amazing things about this country: sun and surf, delectable seafood, great wine, friendly people. Watching Anthony Bourdain’s jaunt through Lisbon on repeat only exacerbated my full body salivation.

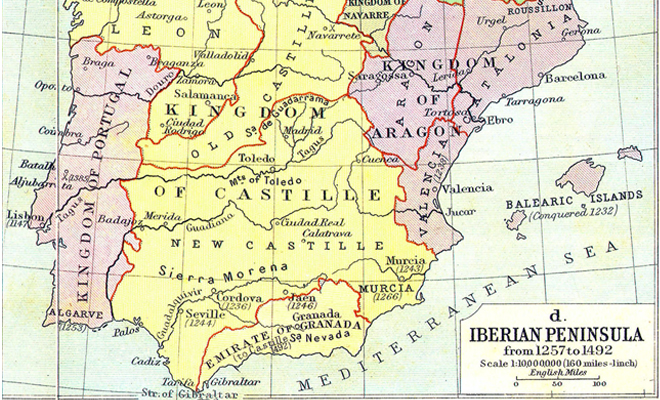

In the pantheon of European destinations, Portugal is easy to overlook. Yet not too long ago, the Iberian Peninsula was the centre of the world, home to the first, longest and arguably most influential empire in modern times. This was the birthplace of the Age of Discovery: a stomping ground of great seafarers and conquistadors, a dynamic hub of global trade and innovation. It was also home to one of the oldest and most revered artisan leather industries on the planet.

In the last century, a lot changed for Portugal – and its leather heritage. Empire became Republic; years of violent revolution and instability; decades of harsh dictatorship under Salazar; a long return to Democracy. Meanwhile, industrialisation modernised and overhauled the old leather tanning industry: new technology trumped artisan techniques, as quality took a back seat to productivity.

Like much of Europe, Portugal is today licking its wounds from tumultuous politics, economic austerity and runaway globalisation. An air of renewal and regeneration now permeates. In moving forward, they are looking back, and a once great leather industry is slowly being remembered, and revitalised.

Fresh players have begun to forge a new leather carry legacy in Portugal: dedicated to reviving the old ways, one bag at a time. It was more than just the rumble of ocean that had been swaying my attention across to the west.

Punching the secret red button under the bust of Shakespeare, I slid down the fire pole behind the faux bookcase and barked down the direct hotline to Carryology HQ. We had a new mission: HK and I would travel to Portugal, meet and interview the new breed of world-class leather carry designers, artisans and tanners, and gain a glimpse into the fresh energy being pulsed into one of the oldest leather heritage regions on earth. Funds were cabled overnight. We set our course for Lisbon.

The Land of Leather & City of Seven Hills

Peppered with sunsets, our days and nights were fuelled with wanderlust in Lisbon, the perfect city to loosen a pasty, Berlin-hardened soul.

“Fresh players have begun to forge a new leather carry legacy in Portugal: dedicated to reviving the old ways, one bag at a time.“

But our carry adventure actually began an hour outside the capital: in Alcanena, the ‘Land of Leather’, traditional heart of Portugal’s artisan leather industry. Both a city and municipality, the first Portuguese leather artisans settled here back in the 16th century, at the doorstep of the Natural Park of Serras de Aire and Candeeiros. Soon after, the first manufacturing tanneries were established.

The Portuguese had a major influence on the development of this industry. With their empire spread across the globe, newly discovered lands in South America yielded previously unattainable vegetable-based substances: natural tannins like wood bark from Mimosa and Quebracho trees, fruit pods, leaves and fatliquors, all of which inspired new methods, mastered over centuries, some still in use today.

On a mild Thursday morning, after a GPS glitch took us a wrong turn off the A1 highway north (a wrath we would again suffer, though far worse, on the return leg) we barrelled from the outskirts of Lisbon in a sleek black Volkswagen rental, bound for the Land of Leather.

We’d organised to meet local fixer, Pedro Fernandes: founder, designer and craftsman of Noise Goods, an artisanal carry label based in Leira, not far from Alcanena. In James Bond style, he said to meet at coordinates 39°28’54.4″N 8°37’30.2″W, which turned out to be a pothole off the side of a highway turnoff by the base of the Candeeiros Mountains, lush and rugged, and today, shrouded in soft mist.

A white van was waiting for us. Inside, a man in a beanie, arm raised, pointing at a leather backpack: international greeting gesture of the carry kind. Genial and welcoming despite our tardiness, Pedro had cleared his whole day to give us a guided, behind-the-scenes insight into his world.

We cruised to nearby Alcanena, a sleepy township of slender streets and bone cobblestone squares, terracotta villas with iron weathervanes. We pulled into a gravel driveway through a rusted old gate, parked, and knocked on the door of a long clay building that looked like it had seen some days: the workshop of artisan leathersmiths Luís and Pedro Caetano, craftsmen behind Noise Goods, veterans of the trade.

(left) Luís and Pedro Caetano (right) Pedro Fernandes

Luís greeted us at the door with a meaty handshake and husky tenor: “Excuse me, my English…very small.” His brother Pedro nodded welcomingly from the far corner. The walls were lined with steel shelves, strewn with mish-mash fabric rolls. Heavy-duty industrial sewing machines down one side, sheet leather cut in shapes hanging in production rows on the other. Down the centre, a long wooden workbench littered with tool blocks, nails, multi-coloured filers and vices. Robert Johnson blues crackled from a radio; I smelled cigarettes, and musty leather.

“I met these guys last year,” said Pedro. “Noise Goods started with wallets, then I expanded to bags. I make the patterns and design…but, working with leather, things get a bit complicated: it’s a stiff material; you have to know how to work with it, and these guys translate it to the real deal.”

He unveiled some recent orders: hybrid backpacks blending local vegetable tan with tough-woven Burel – pure shepherd’s wool from Manteigas, near the Serra da Estrela, the highest mountains in Portugal. The workmanship was the real deal, but it was the vegetable-tanned leather that stole the show.

Vegetable tanning was the original Caetano family business. The workshop was once a commercial tannery, explained Luís, one of the first in the region: their uncle Tio Joao built it in 1935. Hides were treated in the basement, dried upstairs: Luís showed us down a level – no lingering signs of any tannery here, just a man-den of the highest calibre: pool table, curios, bar in the corner stocked with good Port, shields with pistols mounted and crossed.

As the Caetanos will tell you, there’s no denying the superiority of vegetable-tanned leather. Like their forebears, they’ve been working with it their whole lives – a thirty-year career, mostly in hunting gear, trading under the family label ‘Equicaça’. Luís unveiled some of their wares in a tucked-away display room: rifle holders, bullet bandoliers, a leather horse saddle, all handmade, masterfully constructed. Though he and Pedro might look the part, neither has hunted in their lives – this was just a way to make a living, as their father and uncle had done, and theirs before them. Today, they add artisan bags to their swag.

Noise Goods, as well as Porto-based label Ideal & Co – the two local carry houses spearheading a renaissance in domestic heritage production – rely not only on the Caetanos’ exemplary craftsmanship, but insist upon using 100% vegetable-tanned Alcanena leather – an all but forgotten art in Portugal. We’d learn a lot more about this later in the day.

A machine began whirring to life: Pedro, puffing like a boss on a Chesterfield Red. It occurred to me that there weren’t too many workshops around like this anymore, and even fewer leather artisans with a generational legacy to their name. I felt a surge of connection to something true and real here, something close to sacred: an old art in motion, a long-held conversation, still going.

***

The Angelinos Tannery

On Luis’s advice, we enjoyed a hearty lunch at Café Facho, a noisy bistro full of regulars on a street corner by an otherwise sleepy Alcanena town square.

A short drive away took us through the industrial gates of ‘Curtumes Angelinos’ – the Angelinos Tannery – a scrubby yard of worn buildings, some with pitched rooves buckling from decades of sun. I saw fresh tanned hides draped on wooden rungs, drying in the mild air; Portuguese voices reverberated inside a corrugated factory hall. Then, a curt man in brogues and red cord shirt greeted us, eyes intent, almost fierce. Mr Martinho was his name. “There are no secrets,” he said. “We show you everything.”

He led us inside a corrugated factory building where an industrial scudding machine was screaming full bore. The concrete ground was tar black, moist with scunge. I smelt a buttery slaughter smell, sour and acrid, that of animal fat – not unpleasant, though far from ambrosial. “Today is a good day,” said Pedro.

Word of our arrival had spread: Hélder, Martinho’s cousin and partner, a stout chap with a cheeky grin who smoked cigarettes and cracked jokes in good English, joined us. Soon, another cousin: Amorim, a lanky unit with a moustache and slightly hunched gait. As I quickly began to notice, the Angelinos, like the Caetano brothers, are a rarity. They are one of few, in Portugal, who still produce leather the old way – the traditional way: vegetable tan.

For centuries, vegetable tanning was the only way to tan: hides were stretched and then soaked in vats for weeks in a soup of increasingly concentrated plant extracts. With the rise in demand for leather goods throughout the 20th century, chemicals like chromium sulphate began to replace the traditional vegetable process, and the majority of Portuguese, and international, tanneries shifted their production to the modern technology.

There were reasons for this. Vegetable tanning is slow, often taking up to two months for a turnaround. Chromium takes a day or two, a boon for productivity and bottom lines. It’s also more malleable, so it appeals to certain products like shoes, for example, traditionally a big market in Portugal (the region of São João da Madeira, further north, is known as the ‘Land of Shoes’).

“I felt a surge of connection to something true and real here, something close to sacred: an old art in motion, a long-held conversation, still going.“

But labels like Noise Goods and Ideal & Co insist on the older method – vegetable tan makes a product last longer and look better: the natural tannins create a patina in the hide that brings out its intrinsic character, helping it age gracefully, becoming more beautiful over time and use. It also makes a product smell like ‘real leather’ in a way that chemical chrome can’t.

Angelinos are one of just three tanneries in Alcanena still dedicated to the vegetable method. “For a while, we used to be more chromium, maybe 50-50,” said Hélder. “Today, 5% chromium, 95% vegetable.”

In the 90s, the industry suffered a shake-up: Portugal’s admission to the EU drove labour costs skyward, just as an influx of Asian production began to invade the local market. Difficult compromises were made: some players moved offshore, while others tried to compete with the Asian influx. Many struggled: Between 1993 and 2013, 116 tanneries fell to just 61 in Alcanena alone. Others maintained a higher-quality chromium-tanned product, creating niche opportunities in artisan accessories and fashion goods, selling to European markets that appreciated the value of ‘Portuguese-made’.

Though the GFC inflicted further strain on the local industry, ‘Made in Portugal’ is on the rise in Europe – the choice of fashion houses everywhere – and while perhaps not as prestigious as its Italian or Spanish counterparts, it matches both for quality.

So where do the Angelinos fit into this picture? As you can imagine, it’s been a stormy ride for the smaller players in recent decades. But like the Caetanos, the Angelinos have weathered it: they continue to provide an important niche, covering the national supply of artisanal goods like animal straps, belts, and wallets. While they tan small batches of chromium to remain competitive, they remain dedicated to their vegetable heritage, thriving on the support of brands like Noise and Ideal & Co, who understand the importance of revitalising their ancestors’ techniques.

“There is a heritage in shoe leather here, but not really a bag heritage,” said Pedro. The heritage carry legacy in Portugal may have just begun.

“‘Made in Portugal’ is on the rise in Europe…and while perhaps not as prestigious as its Italian or Spanish counterparts, it matches both for quality.“

In the rear of the factory stands Angelinos’ original building, a cloistered room with pitched bearings, bowed and wavy, buckled by the ravages of time. I asked Hélder and Martinho how old the place was. They bounced off each other, but couldn’t reach a consensus. Pedro cut in. “Their uncle is 93 years old,” he said. “He started here when he was 10. And when he started, it was already really old.”

Martinho then stood behind a wide bench, swabbing and waterproofing a hide with a crimson paste. In an adjacent workroom, two workers dipped tin jugs into vats of animal fat – by-product of the tanning process – pouring generous dollops into empty plastic canisters placed across a large table. One of the pourers directed something at me in fast Portuguese. The others laughed. “He says he already ate a Kangaroo once,” said Hélder, referring to my Australian heritage. “It’s not bad.”

Hélder spied my boots, also made of Kangaroo, the leather tops dry and cracked. “You have to make some fat in there,” he said, offering me two batches of the Angelinos home blend. (My boots have never looked better since). Amorim returned from the stock room with a pair of leather ballerina shoes, gifting them to HK. “For your dancing,” Pedro said, smiling. Amorim then sized up my waist and gave me an authentic black Angelinos leather belt. More gifts from the Kings. We shook hands and thanked our new friends, the leather men of Alcanena: lion-hearted and steadfast, dedicated to the fundamentals in an ever-shifting modern world.

“…vegetable tan makes a product last longer and look better: the natural tannins create a patina in the hide that brings out its intrinsic character, helping it age gracefully, becoming more beautiful over time and use.“

***

We drove back through Alcanena central and took a pit stop at the local Municipal Council building. There, we engaged in an illuminating chat with an energetic woman in a salmon scarf: Aida Costa, the council communications facilitator. Educating us about all things Alcanena, she proceeded to choc-ram a plastic show bag full of promotional collateral for further research; it would double the weight of my carry-on luggage. She then holed up Pedro, coaxing his patronage at the upcoming Alcanena municipal leather fair.

The day now waning, we cruised behind Pedro a half hour to his home and workshop in nearby Leiria, a cosy setup. On the wall of his studio, a framed picture with an embedded slogan: “Be Nice & Make Noise.” I wondered if it inspired his brand.

“Well…actually, it’s something kind of ridiculous,” he said. “I was listening to a band, Sewn Leather, who play ‘noise’ music. So I responded with ‘noise goods’.” For further clues, we might look to his brand manifesto too: “to use less resources and more our own voice”, in a sense: to make noise, by choosing well-made products that last long and don’t harm the environment – rejecting the ordinary, the disposable, and instead forging solid relationships with simple, quality products.

“…the leather men of Alcanena: lion-hearted and steadfast, dedicated to the fundamentals in an ever-shifting modern world.“

He showed us some of his latest, and some classics: the original Noise coin wallets, the design that sparked his entire carry enterprise. Kind to the last minute, he offered HK and I a hand-sewn wallet each as a parting gift.

Though we’d have preferred to stay in Leiria and hang out with Pedro and his cat Pudding all night, we had to return the Volkswagen to Lisbon. We thanked our new pal for his hospitality and kindness, and promised we’d meet again. Then we took off back down the highway to the sun-soaked capital, brimming with inspiration, coddled by seductive sunset vistas of lush, rustic Alcanena, the Serra dos Candeeiros stoic and mighty in the rear view.

*Photography by Honor Kennedy

Carry Awards

Carry Awards Insights

Insights Liking

Liking Projects

Projects Interviews

Interviews