Meru :: First Ascent of the Shark’s Fin

For a Carryologistst, watching outdoor films is as much about the adventure on the screen as it is the gear on the athletes’ backs. It touches upon the endless debate, to what extent are expeditions dictated by the gear we take with us? Can gear make up for a lack of outdoor experience and allow us to achieve things that would otherwise be unattainable? Would that summit have been attainable with a lighter backpack or a bit more gear? It’s a question that becomes more black and white the more extreme the adventure gets. And it’s a question that swirled through my head when I found my seat to watch the film Meru.

The 2015 film Meru captures the 2011 summit of the Shark’s Fin peak. A 1,500′ vertical rock wall on Meru Mountain, a rugged 21,850′ mountain in the Indian Himalayas. The film chronicles Conrad Anker, Jimmy Chin and Renan Ozturk’s second attempt to summit the peak after their failed 2008 summit.

Alongside gorgeous cinematography and the stomach-churning heights that grace Meru, you’ll spot the ubiquitous The North Face logos. On the bags, the helmets, the jackets, the portaledge, everything. Curious about what went into making The North Face gear used to achieve the first summit of the Shark’s Fin, I caught up with The North Face designer Ezra Liang and The North Face lead climber Conrad Anker over the phone to talk shop.

“Can gear make up for a lack of outdoor experience and allow us to achieve things that would otherwise be unattainable? Would that summit have been attainable with a lighter backpack or a bit more gear?”

Why custom?

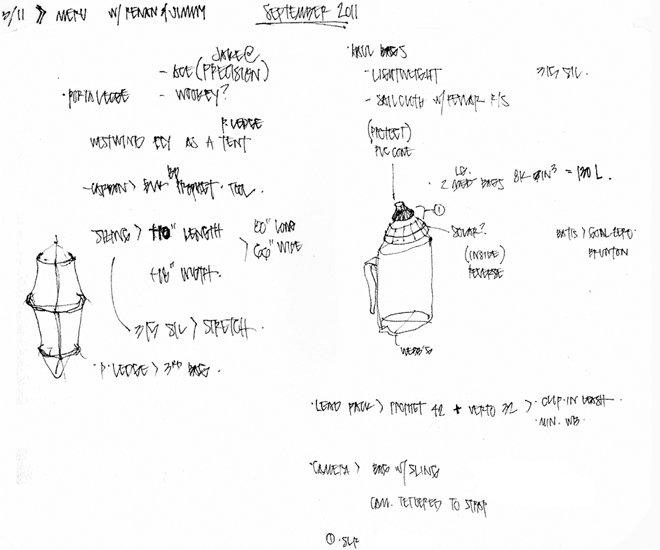

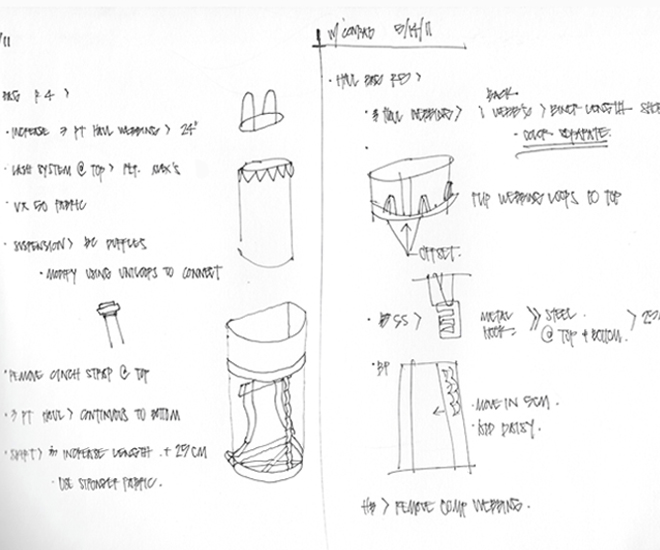

It comes as no surprise when Ezra begins by explaining that The North Face products seen in Meru were completely custom, and the result of a very specific and singular design focus. The culmination of six months of coordination across numerous design departments at The North Face. The goal: to balance Conrad, Jimmy and Renan’s limits with what is possible in gear and carry design – to custom build the gear to last the expedition, and no more.

The successful summit of Meru was a long time coming. It was an iterative process both in the approach taken to the summit and the gear used. “The first time Conrad, Jimmy and Renan attempted the summit, they tackled it very gungho. They tackled it in the way a lot of our athletes do. They set up the expedition and then just picked things that we had in our product line. There was nothing custom about the gear,” Ezra tells me. However during the first summit attempt, the complexities and difficulty of Meru proved to be too much, “The team got turned around after 19 days, 100 meters from the summit.” Though tantalizingly close, they were still very far away. “They realized they needed to come at it from a much different point of view, a different attack strategy.”

“The culmination of six months of coordination across numerous design departments at The North Face. The goal: to balance Conrad, Jimmy and Renan’s limits with what is possible in gear and carry design – to custom build the gear to last the expedition, and no more.”

The Anti-Everest

The Meru peak had remained an elusive first ascent for good reason. It’s described as the ‘Anti-Everest.’ There are no Sherpa teams to set rope, it’s remote with no basecamps for support, and up until Meru it had very little international notoriety. That and it’s just plain hard. “It’s hard in this very complicated way,” explains author Jon Krakauer, “you’ve got to be able to ice climb, mix climb and you’ve got to be able to do big wall climbing at 20,000′. It’s all that stuff wrapped in one package that’s defeated so many good climbers.”

The Second Attempt

“Once back stateside the guys came to the The North Face offices and were like ‘We’re going back, right away, this is our timeline,’” Ezra continues. During the first ascent there was so little intel on the route that they had to take a more ‘siege tactic’ approach to their ascent. “Their gear was heavier than usual and they carried more supplies given the complete lack of beta about the wall.”

“The Meru peak had remained an elusive first ascent for good reason. It’s described as the ‘Anti-Everest.’ There are no Sherpa teams to set rope, it’s remote with no basecamps for support, and up until Meru it had very little international notoriety. That and it’s just plain hard.”

During this meeting it was immediately agreed upon that to be successful in their second summit attempt, the guys needed the lightest and most streamlined kit possible. “It was like, we’re about to put all hands on deck at The North Face to make a complete custom kit; get ready. We were going to streamline Conrad, Jimmy and Renan from head to toe. From the apparel to the way they planned their meals to the equipment we designed for them,” Ezra recalls excitedly. “This was their second time attacking the mountain. They knew where they could make sacrifices in their gear and where they couldn’t. This was the theme throughout the entire design process.”

“During the first ascent there was so little intel on the route that they had to take a more ‘siege tactic’ approach to their ascent. “Their gear was heavier than usual and they carried more supplies given the complete lack of beta about the wall.””

“There was a genuine willingness to make our second summit attempt a success,” notes Conrad. “During the first attempt the team at The North Face followed us very closely. We were off the radar for 19 days and everyone thought we had died. When we finally came back and told them that we were three pitches away from the summit, there was an instant understanding back at The North Face. ‘We’ll make you guys the best gear possible to make the second summit attempt a success.’”

Over the next six months the designers at The North Face aimed to match the limits of their gear with the athletes’ physical boundaries. “They sat down with the baselayer team, the summit team, the equipment team and just worked through the entire kit.” Everything was about how to make them move as efficiently as possible. “It was really something special the way everyone at The North Face was focused on this assignment,” recalls Ezra. “Only designing the kit for the 2014 Winter Olympics had this level of coordination from the company as a whole.”

“…to be successful in their second summit attempt, the guys needed the lightest and most streamlined kit possible.”

This design process went much deeper than simply choosing where to put pockets or what size backpack to take. The Meru gear was going to question what was possible or not. “Building the gear for Conrad, Jimmy and Renan was a much different process than how we at The North Face design our consumer line” explains Ezra. “For starters this gear didn’t need to last five years, but one month. The bags the guys carried had to get up the Shark’s Fin just once. Literally just once. The bags would then be tossed down the mountain during the descent.” In general this allowed for a much lower denier and lighter fabric to be used along with stripped-down support and padding.

The Sacrifices

“But it’s a fine line,” Ezra quickly notes, “the minute you start taking away weight, you start sacrificing durability.” You’ve got to be clear, “how much comfort and durability are you ultimately willing to sacrifice for lightness? These athletes are so tuned in with how their bodies work, what their bodies can handle, and what their limits are, they tend to stretch their limits as well as our design limits. As designers we’re often not comfortable with what they’re asking us to do. These expeditions are literally a life and death thing. How do we design for the expedition mentality of these athletes – accepting a certain level of suffering and physical discomfort in order to move faster – without having the gear jeopardize the expedition?” In other words, when does the bag on your back become a necessity or a hindrance to an expedition? On the Carry front the team took a handful of bags up the Shark’s Fin, each designed to toe this line.

“For starters this gear didn’t need to last five years, but one month. The bags the guys carried had to get up the Shark’s Fin just once. Literally just once. The bags would then be tossed down the mountain during the descent.”

Haul Bag

To carry the bulk of supplies up the wall each guy hauled a 100L haul bag. Because these bags were literally dragged up the mountain they needed to be very abrasion and tear resistant. “After some unscientific tests dragging prototypes around The North Face parking lot behind a truck with a conventional fabric” Ezra explains with a laugh, “it was decided that a stronger fabric was needed. Eventually we settled on 1000D X-Pac fabric from Dimension Polyant.”

“The haul bags were really good, much better than the first ones we took up,” Conrad adds in. “The old ones were made out of hypalon which meant that when they got cold the bags were stiff. But not stiff like cardboard, stiff like ¼″ plywood. They were horrendous to fiddle with. Having a cold polyant fabric on the new haul bags made all the difference.”

“How do we design for the expedition mentality of these athletes – accepting a certain level of suffering and physical discomfort in order to move faster – without having the gear jeopardize the expedition?”

While X-Pac is not economical in the consumer product lines at The North Face, it made sense here. “The abrasion tests were just off the charts. You could daisy chain them off each other. We saved a ton of weight with the X-Pac construction. And best of all when these guys would throw these bags down the mountain before descending, we knew the construction would hold on impact so the bag wouldn’t explode and you have a yard sale all over the bottom of the mountain.”

When I ask what became of the haul bags Conrad laughs, “The haul bags were great and held up incredibly on the mountain. But back home in Montana I had the bags sewn into briefcases. Jimmy, Renan and myself each have one.”

Backpack

For the trek to the base of the Shark’s Fin the team grabbed the design from the Prophet 65 Summit Series backpack and constructed it with The North Face exclusive silicone coated 315D Cordura blend. Getting technical, Ezra notes that this fabric is very similar to the airbag fabric used in the automotive industry. “We knew that this Cordura blend was very durable for its weight and denier, so we chose it to build these packs with. The only thing custom about these packs was the fabric but the guys were comfortable with that.”

Summit Packs

For the all-important summit of the Shark’s Fin it was decided to take the Verto 35L from the Summit Series and size it up to 50L. But like the usual 35L Verto, this custom 50L size had to still stow into a compression sack before the team attempted the summit. “I told them when they asked for a 50L summit pack,” Ezra warmly notes, “that’s a lot of weight you’re carrying on a minimal suspension with something like a 1cm thick foam back panel. That was it. Again it’s this expedition mentality. They know a 50L pack with a 1cm back panel is not going to be comfortable but they’re okay with it.”

Perhaps not surprisingly the pack carried horribly. “They ended up leaving the summit packs at the base before they even started the summit” laughs Ezra. “And that’s the end of the Verto 50L. We learned that our limit for a minimal suspension build is about 35L.” This is a case of a design that even the expedition mentality can’t justify.

Camera Packs

While The North Face doesn’t make any camera bags in their lines they put two together for Renan and Jimmy. These bags were tasked with holding the camera equipment that shot the whole of Meru. The packs were designed in three pieces; a small bag to hold a DSLR with medium lens, an oversized waist pack for another DSLR and three lenses with batteries, and a travel box with backpack straps to house the cameras while traveling.

“‘We learned that our limit for a minimal suspension build is about 35L.’ This is a case of a design that even the expedition mentality can’t justify.”

Material-wise the packs were constructed from a 200D sailcloth weave with a lightweight foam. “This foam was really lightweight, really great” explains Ezra. “We had heard of this foam but it was something we weren’t comfortable with building into our regular products because we hadn’t tested it enough. It’s a bit more expensive than our traditional EVA foam but almost half the weight. It’s a great way to shave weight and since cost wasn’t an issue with this gear we were willing to pay what we needed to make a product that would save a few ounces.”

Despite the camera bags being a new foray for the designers, they have achieved a significant milestone with this pack. As Ezra explains, “The one thing that I’ve learned from working with all of these athletes is that a lot of the time they don’t bring product back. They go on these expeditions and leave the product with the Sherpas or the porters or leave it with friends.” “In a region like Uttarakhand [the Indian state where Meru is located],” continues Conrad, “you have all these people living in a harsh environment and they could genuinely use a sleeping bag or a backpack.”

“Despite the camera bags being a new foray for the designers, they have achieved a significant milestone with this pack.”

“Unless it’s something they’ve fallen in love with or something we ask for back, most of the time they leave it with the people who have helped them get up and down these mountains. So we’ve realized that if they do bring something back, that’s when you know that they really like it,” notes Ezra.

And that’s just what’s happened with these camera bags. “To this day Renan and Jimmy both still use the bag. When they are doing a loadout for an expedition I’ll see the camera bag in the kit they post on Instagram. I’ve asked them to bring it in multiple times and they refuse,” laughs Ezra. “They won’t let me get my paws on it. I promise them all I want to see is how the fabric is wearing!”

While the design process behind the custom Meru bags is not ordinarily done at The North Face, it’s very much in the DNA of the company. It echoes back to the mentality of the climbing community in the 1960’s. “That’s their roots,” explains Ezra. “Nobody knew what kind of equipment they needed. You look at (The North Face Founder) Doug Tompkins, Yvon Chouinard and Royal Robbins, when they were pioneering routes in Yosemite they were making their own equipment and own gear.”

“While the design process behind the custom Meru bags is not ordinarily done at The North Face, it’s very much in the DNA of the company. It echoes back to the mentality of the climbing community in the 1960’s.”

While Conrad, Jimmy and Renan weren’t sewing their own bags or welding their hardware ahead of their Meru summit (though Ezra notes some of them can stitch a bag quite nicely), there’s an undoubted similarity to the ‘60’s mountaineering fluency to the gear and carry that pioneered new summits. “We brought them in at every proto-stage to physically work over the samples,” notes Ezra. “We don’t just ask them what their dream list of pack features is, but to really articulate what they need in their gear.”

“These guys can pinpoint the construction of a tent that we’re prototyping, say the corner of a tent, and say that ‘this construction is going to blowout because I’m going to be in 100 mph winds and the tent will be rubbing against the rock that I will need to anchor the tent with. I’m going to need to fix this in the field unless you guys change it,’” laughs Ezra. “It’s a blessing and a curse working with athletes that are this knowledgeable about their gear.”

When what you carry begins to affect how you work

Perhaps this fluency in the gear on our back is ultimately required when we find ourselves working in the extremes, like 1,500′ up Meru’s Shark’s Fin. Literally at the edge of the world. In the world of Carry this is when things get interesting. When what you carry truly begins to bleed into and affect how you work. What are you willing to sacrifice in your carry and when do you have to make sacrifices for what you need to carry?

“Perhaps this fluency in the gear on our back is ultimately required when we find ourselves working in the extremes, like 1,500′ up Meru’s Shark’s Fin.”

I pose the question to Conrad, could Meru have been climbed 30 years earlier? Without a pause he replies, “Oh yes, if someone had the right equipment. It’s not so much a mechanical problem. You figure, for instance, that a portaledge had been around for decades before on El Capitan. It’s more of having a willingness to take the gear to the extreme.”

Ultimately what makes the Meru expedition fascinating from a carry perspective is not new innovation or material that went into getting the guys to the summit, but pushing The North Face gear to the extreme. Having Conrad’s climbing pushing the limits of Ezra’s designs. “Ultimately all the mountains will be climbed, everything is finite on this planet,” muses Conrad.

“We’re great engineers, especially the guys at The North Face. But if it’s a matter of simply engineering a way up the mountains, put enough money and resources into making a summit and you will make it to the top of that summit very quickly. So instead you’ve got to choose to make the summit with less equipment. In our case [on Meru] we didn’t fix rope or use power drills. We climbed the mountain on its own terms.” Ultimately it’s not the technical designs of The North Face packs and space age fabric that helped achieve the summit of Meru, but Ezra and The North Face designing bags to allow Conrad, Jimmy and Renan to face the mountain on their own terms. “You have a greater experience when you do that,” Conrad concludes.

“Ultimately it’s not the technical designs of The North Face packs and space age fabric that helped achieve the summit of Meru, but Ezra and The North Face designing bags to allow Conrad, Jimmy and Renan to face the mountain on their own terms.”

Photos used with permission from The North Face, Conrad Anker and Ezra Liang.

“How Conrad Anker Risked It All to Chase a Dream.” Outside Online. June 18, 2015.

Carry Awards

Carry Awards Insights

Insights Liking

Liking Projects

Projects Interviews

Interviews