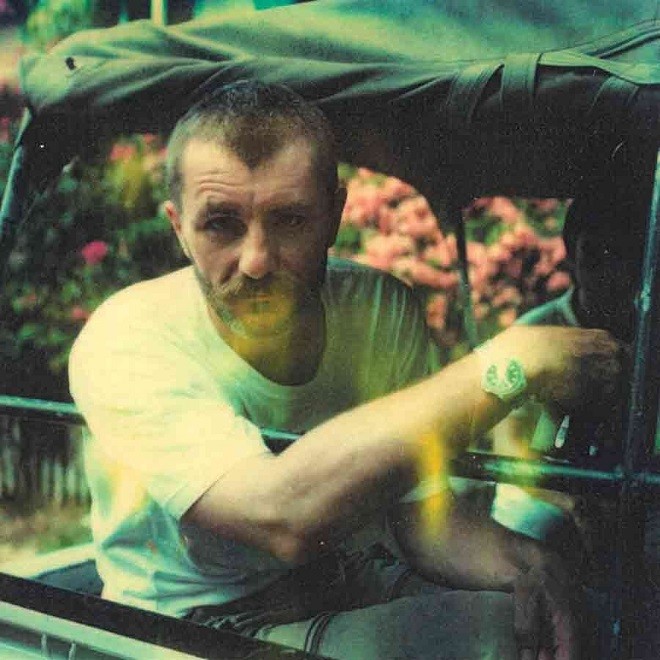

Specialist Carry: War Zone Reporter

Robert Young Pelton has journeyed to more dangerous places than any man on the planet. A former marketing exec, turned adventurer, inventor, journalist and author of the New York Times best selling books, The World’s Most Dangerous Places; Licensed to Kill: Hired Guns in the War on Terror and Come Back Alive, he’s covered 14 wars and visited 130 countries, by last count.

In his career, kidnappings and assassination attempts have been a reality. He can now tell the size of a cartridge by the sound it makes as it slices the air above his head. And he knows that in warzones you hang out with the guy with the grey hair; he’s the one who teaches you how to stay alive.

An intrepid traveler and gnarly human being by anyone’s measure, RYP’s wealth of experience in life, travel and survival is unmatched. So, we asked the great man to be our next subject in this month’s Specialist Carry…

You weren’t always the war journalist. A lifetime ago, you left your executive job in pursuit of adventure. What was the catalyst? What flicked the switch for you?

Well, first of all, I was a guy who lived in a car when I was 16, a Rambler station wagon, and I picked fruit. So I didn’t have a lot of chances to do things. But you know, once you get the “poor guy” mentality, you tend to focus on making money. I had no university education, I had no formal education. But I found I had a talent for marketing and advertising, and I built up an ad agency called Pelton Associates, which I think was #126 on the Inc. 500 list. I worked with Steve Jobs on the launch of the Macintosh. I launched the Upper Deck Trading Card Company. In my last job, I was paid $500,000 a year by Marvel just to answer the phone. And I was in my late 30’s, 40’s.

Along the way, I had a number of mentors. In a very short span of time they began to die. My father died of Lou Gehrig’s Disease, which is a debilitating disease, which, you have like six months to get to know your father and talk about life and this and that. A client of mine had bone cancer and was told he only had a few months to live.

And I realized that if I didn’t start doing what I really wanted to do, I would end up just being in the middle of something and dying. And I used to take a month off, and picked the most remote place on the planet and went there. And I was blissfully happy. I thought, “You know, I should be doing that thing that I escaped to do one month out of the year, rather than 11 months a year making money.”

And that goes against normal, rational thinking, which is that you need to make money. It’s a trampoline. You make money, you make more money. And at the end of the day, you’re just going to be making money. You’re not actually going to be focusing on the things that make you happy, that give you wisdom, that help other people.

I realized that we don’t have much time in the world, and if you don’t do exactly what you want to do now, you will never do it.

And what happened next?

I left my job and went to Africa and started writing about the places I was in. Next, I bought a publishing company, because I figured that’s what people with grey hair did. And I wrote a book called The World’s Most Dangerous Places, it was a 1,000-page book about how to get into all of the world’s war zones, and how to link up with rebel groups, etc. And it was a very funny book about how to enjoy life and basically not worry about danger and death and all these things that we fear. That book came out in 1993. I felt that it was time for me to do the thing I wanted to do in my 40s. So essentially I took that book and what I wanted to do, and I branded myself.

“I realized that we don’t have much time in the world, and if you don’t do exactly what you want to do now, you will never do it.”

So within six months I had a huge, special documentary on me by ABC News with Bob Woodruff called The World’s Most Dangerous Places. And they were supposed to follow me to the world’s most dangerous places, but they kept bugging out and it never got made.

But I just kept filming. That footage became the concept for my Discovery Channel series called The World’s Most Dangerous Places. And I got a two-book deal from Random House to do my autobiography. And so it was in those six months to a year when I was suddenly doing what I was doing for other people; I was my own brand. I was the guy who was not afraid to go anywhere, and trying to give some kind of insight and wisdom to people who wanted to deal with the world’s most dangerous places.

Totally. You only have one shot. You might as well go for it!

Exactly, yeah. If you screw it up, that’s fine; at least you tried. But we don’t lie in our deathbed and think, “Thank God I made it to the office by 9:00 for 25 or 30 years,” you know?

Okay. But we’ve gone from marketing man to a writer specializing in dangerous places and war. But I’m curious about in-between. What was your first war zone?

The first war zone I guess was when I went to eastern Turkey to meet the Bucak family. They were Kurdish militia and were involved in all kinds of nefarious things like trying to kill the Pope. I remember they didn’t quite know what we wanted. I was there and I was writing about them, and so they thought, “Well, let’s have a shooting contest.” And unfortunately, I was pretty good with a gun, so I hit the Pepsi can, and I remember Sedat Bucak ordering his bodyguard to go over and execute the Pepsi can that he missed, and I thought, “There’s a lesson learned!”

Carry tip: “be prepared to give away, lose, or not-figure-out-where-it-went with everything you bring”

So I did that, and I went to Algeria to meet the GIA, which was interesting, because I went there as a tourist because they wouldn’t give me a journalist visa, and I was the only tourist in this rundown, old hotel during the elections. And I got a chance to go out to what they called the Triangle of Death, and meet with people. And I was really impressed with how hard people worked to get you to understand the truth.

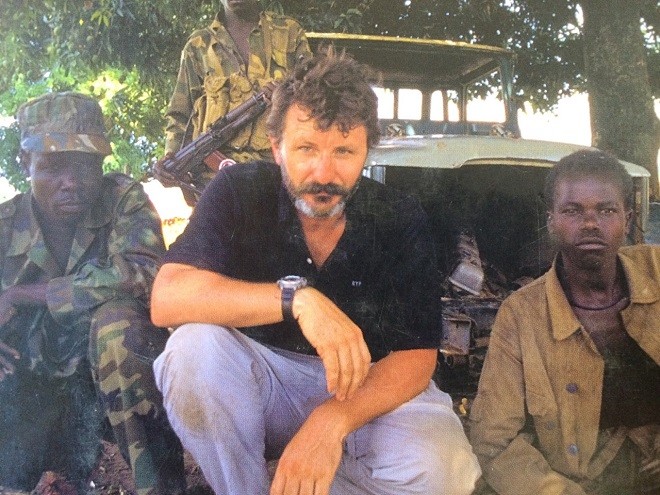

And I have to say that that was back in the mid-90s, or early 90s. And I became more and more convinced that there were places on this earth where they deliberately create fear to keep people out. You know, whether it’s Syria, or in places where they do kidnappings like Chechnya. So my specialty became the “dirty wars,” the ones that nobody wanted to go to, nobody wanted to write about. And I would go in with the rebel groups, and I’d be in combat with them and live in the trenches or whatever. And I would come out and write a book – no short stuff – and then at least provide some insight into why that war happened and why it was occurring.

And what do people misunderstand about your work?

One of the things that people don’t seem to understand is the actual journalists who are in combat with rebel groups versus journalists who are doing embedded or slightly glamorized versions of what we call “war reporting.” It’s very different. One of the things that I’ve always tried to do is not focus on the gruesome or the dead bodies, but to focus on the normal people and the stories of what it’s like to be in these wars. People say, “Gee, you must be brave. You went to three dozen wars!” But in every one of these wars, there are grandmothers and little kids. So I don’t try to prove to people that I’m braver or smarter or stronger. I just want them to understand that war does not have front lines anymore, that “war” can be Downtown New York City, it can be the subway in London, it can be a coffee shop in Sydney, so on and so forth. I think what I’ve tried to do – and if you saw the last thing I did, which was Saving South Sudan – is to cut against the grain of what we call “war coverage,” or whatever it’s called. It really gets you to feel bonded with the people who are caught in conflict, whether they’re murderers or whether they’re children or ladies, and realize that “Oh my god, this is part of everybody. It’s not something that happens over there. It’s part of the human experience.”

Totally. Do you feel a responsibility to be that person to go in and do those things that not many would, so if you can, you will?

Well, I do it because I’m comfortable doing it. So it’s not like I have a job [chuckle] or I have to do it. I read the news a lot, and I see something that doesn’t make sense, and I dig into it and think, “Okay, I need to go there.” I’m not an activist, I’m not a hippy, I’m not trying to prove anything. I’m just trying to create a little window into these places that is historically accurate and maybe neutral, so that a year from now or ten years from now you can go back and read my books and go, “Wow, that was what it was like.”

“…we don’t lie in our deathbed and think, “Thank God I made it to the office by 9:00 for 25 or 30 years,” you know?”

You’ve been to all these war zones and been behind these lines for many years now. What tools would you take with you on a regular basis?

Okay. So here’s the thing. Westerners are weird people because they bring stuff with them. I’ve always been amazed that when people bringing something from a civilized country into a “war zone” or “famine zone” get there, they suddenly realize that everybody around them has nothing but still survives. So the “culture of stuff” always impresses me.

Secondly, the idea that that’s your stuff and not their stuff is really kind of humorous, because what is it that prevents them from saying, “Hey, that’s my stuff.” [Chuckles] The primary rules are: be prepared to give away, lose, or not-figure-out-where-it-went everything you bring; and secondly, learn from the locals: where do they eat? how do they sleep? You know? Do you really need a sleeping bag, do you really need a flashlight, do you really need sunglasses? So I strip my stuff down to the bare minimum with the full expectation that I’m going to give away almost everything I bring.

Wow.

Well, don’t forget. You know, I travel with people where I say, “Let’s go for a week in the mountains,” and they’d take a plastic shopping bag and put in a spare pair of underwear or toothbrush and then walk out the door.

I think Westerners are obsessed with stuff, and there’s no shortage of stuff that you’d buy when you go on a trip. And one of the most healthy things that ever happened to me – and people don’t believe this, but it’s worth understanding – I’ve only had all my stuff stolen in one country and in one time, and that was at the Vatican. This is absolutely true. I parked my car in a parking lot, and I went to take the tour of the Vatican. I came back and all my stuff was taken out of the trunk. And I looked up on the hills, and there were all these kids just waiting for a dumbass tourist like me to put all their stuff in the trunk, and they knew I’d be gone for two hours. But the funny thing is that it was extremely liberating to have no stuff. And so I had another four or five days to travel around, and I thought, “I don’t have any stuff. I can walk anywhere, I can do anything I want. If I need something, I’ll buy it; or maybe if I think I need it, I don’t really need it.” So it was funny getting on the plane because people were suspicious, ’cause when we came through customs, like, “Where’s your stuff?” And I’m like, “I don’t have any stuff. It was stolen.” And they were like, “Well, how do you travel without stuff?” And I’m like, “Actually, it’s quite easy!”

Wonderful. The problem here is that our readers love stuff! [Laughs] Let’s maybe think about journalism tools. You’ve got shells going off and bullets going over your head. How do you get all these crazy happenings down?

I used to use a little Psion, a weird little AA-battery powered sort of notebook. Now I use the mini iPad, because my humongous gorilla hands can type in real-time. I used to use my phone and people thought I was ignoring them and texting people. But you can also record on your telephone. I mean, the iPhone has a perfectly good recording capability – the iPhone has really become the be-all and end-all. I mean, I’ve got my transit compass, I’ve got my locator beacon with my satellite text all in my iPhone. So I basically live through both a small iPad and an iPhone. One is backup for the other.

Great. And do you have any sort of portable batteries or anything like that?

Yeah, I have a big chunky recharger. I haven’t had much luck with solar rechargers or whatever, but you know, when push comes to shove, I’ve got the old pen and paper as well, but that’s kind of old-school. So these days, if you want to keep track of things, I’ve moved from the notebook to the iPhone… Tom Hanks makes this funny little app that looks like a typewriter. It’s called a “Hanx writer.” When you type on your phone it goes chi-ching chi-ching chi-ching! So people don’t think I’m sending texts to my friends or something. It’s kinda fun.

“I strip my stuff down to the bare minimum with the full expectation that I’m going to give away almost everything I bring.”

And you do have to keep contemporaneous notes because the mind is very strange in combat, because what you focus on has got nothing to do with what other people remember. So I also do a lot of video-taping. I used to carry a camera around all the time, which is how my TV series and documentaries started. And you’re always surprised at what you completely missed while you were filming.

You’ve written this book on dangerous places, and survival tips and how to survive. But who taught you how to survive? Was there a mentor there who taught you how to survive?

[Chuckles] Yeah. So, if you read The Adventurist, I had a very brutal childhood. I then was sent to probably the most deadly school on the planet, which was called St. John’s Cathedral Boys’ School, which killed 12 students, one teacher, and was famous for a guy actually coming back to life from the dead after eight hours. And we used to canoe 1,000 miles every Summer and snowshoe 30-50 miles in the Winter. We raised animals, slaughtered them, processed them into ham or whatever, sold them door-to-door. We studied Ancient Latin, French, Ancient Greek. I mean, it was an insane school.Carry tip: carry a fake wallet with a couple of token bills, just in case someone asks for (or demands) it.

But what you do is you go through so many life-changing or life-threatening experiences that you’re just basically done with the idea that you’re going to die. Combine that with respect for people. I mean, I don’t know if you’ve been to combat, but the old guy with the grey hair is the guy you hang out with, and he’s the one who teaches you how to stay alive.

Any mantras you picked up along the way?

The most dangerous thing in the world is ignorance. So if you don’t know something it’s likely to kill you.

Secondly, never follow an idiot who wants to lead an expedition because if any guy wants to get famous by making you suffer, that’s probably not something you want to do.

And there’s nothing that can’t be solved by large amounts of cash or ammunition. There are certain truisms that work in every nation.

“People say, “Gee, you must be brave. You went to three dozen wars!” But in every one of these wars, there are grandmothers and little kids. So I don’t try to prove to people that I’m braver or smarter or stronger. I just want them to understand that war does not have front lines anymore…”

You’ve written in depth about bribes and how to grease the right palms. What are the basics there?

Well, first of all, I liken it to your first dance in high school. Neither one of you quite knows what’s going on, but if you pay attention to how the other person is leading, you’ll get through it. So, bribery is actually what we call patronage. So, in this country, in America, if I get caught speeding, and I say, “Well, look, if I go to court, it’s going to cost a little money here. Here, take $100 and we’ll be done with it.” They’ll throw me in jail for bribery.

Now, in a third world country, they offer to take the fine back to the courthouse for you. So they facilitate the idea that they’re doing you a favor by letting you pay them as opposed to going all the way into jail. But as soon as you act like a dick, trust me, you’re going to be in jail and it’s going to cost you a lot more money. So, in some countries, whether it’s Pakistan or Malaysia or whatever, the idea of facilitation through economic means is the accepted way of dealing with things. So bribery is not necessarily an evil thing. It’s like when you tip a waiter, and you want a good table and you slip the guy $20, is that bribery, or is that just to ensure better service? I’ll let the traveler decide on the legal merits of that.

You make a good point, for sure, ha!

You meet so many dangerous men so often, and you’re there to get information or to learn something from them. How do you earn their respect quickly, and how do you even make them like you in an instant?

Okay, well, there are some very simple things. One is you should always make your introductions through someone they know that can vouch for you. Secondly, you should never lie. You should never tell them that you’re going to do one thing and that you’re going to like who they are. And then thirdly, you should share all the risks with them. And that’s one thing that has really helped me throughout my career, is that I don’t ask to sleep in a bunker. I sleep above ground where everybody is getting killed. I spend my dinnertime in the trenches, not back in the safe area.

“…you go through so many life-changing or life-threatening experiences that you’re just basically done with the idea that you’re going to die. Combine that with respect for people. I mean, I don’t know if you’ve been to combat, but the old guy with the grey hair is the guy you hang out with, and he’s the one who teaches you how to stay alive.”

So, once they see how you deal with their environment, they’re more inclined to say, “Okay, well this guy gets it. This guy understands what we’re doing.” You don’t necessarily have to agree with what they do, you just have to tell the truth. And when I went in with Bin Laden’s people, whom I met with in London, they told me that they were going to give me access because 80% of what I wrote was true. And I said, “Fuck you, 100%.” They said, “80%, that’s not bad.” I had to do a bunch of very strange things to make sure I wouldn’t be kidnapped. And there was a French journalist who went in at the exact same time that I went in, who was kidnapped and then chained to a radiator and later killed himself when he got out. So these things are critical.

Wow. How do you keep your edge? Most would lose it after just one war zone.

Well, I think most people don’t realize how many close calls in their boring lives – like, how many times you almost get rear-ended on a freeway, the couple times that that waiter sneezed in your soup, and so on and so forth. If you read Dangerous Places, what you’ll learn instantly is that the concept of danger versus fear are two different things. So, if I’m in a war and people are shooting at me or dropping bombs and there’s an air strike, and I’m watching the bombs falling – I know if they’re oval or round and whether to move or stay – that’s all manageable risk. But if I’m sitting in a plane going to a business meeting, or in a taxi, that’s not a manageable risk. And I think most people don’t realize that once you are focused on mechanics of death and ballistics and explosives and kidnapping or not being kidnapped, it’s actually a very easy thing to manage, versus this sort of nice, soft, comfortable life we live in that has pretty much the same dangers, except we don’t manage them.

Statistically, you’re more likely to die slipping in your bathtub with a big injury than you are in a terrorist attack. I won’t encourage everybody to go get crazy in their bathtub, but what will kill you is not necessarily what you fear.

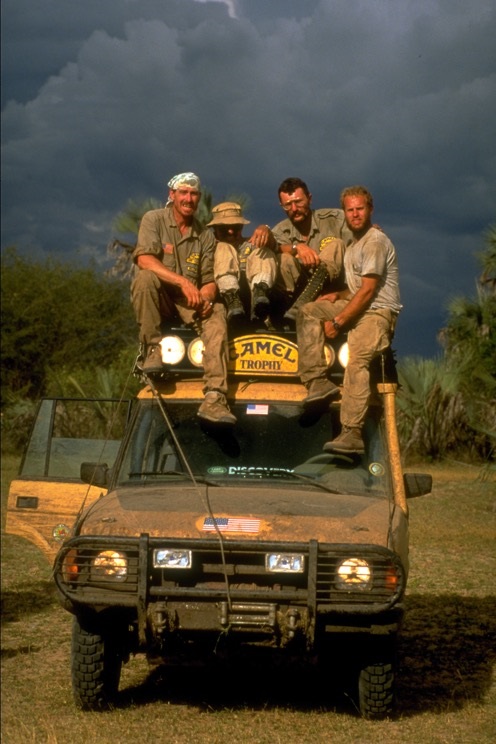

You’ve met so many different kinds of soldiers from militia, mercenaries, Taliban, people I’d fear, ha! But besides the mil-spec gear that they wear and obviously the weapons that they carry, have you noticed or observed them carrying anything in common, like personal items or trinkets or lucky charms?

Well, I think a pocketknife or a knife tends to be the most singular and telling part of somebody’s gear. I did secret missions with special forces guys and was always impressed with why they carried a certain knife, because you know, the odds of using a certain knife in combat are slim. But it’s their sort of touchstone, right? And I would look at these knives and say, “Okay, he carries that because it was his grandfather’s knife, and he served in World War II,” and “This guy carried one his wife gave him.” So they’re sort of talismans that people carry, that they feel will keep them safe, or that will be functional. And if you’re in combat with military people, and like women talking about dresses, they’ll compare gear, boots, socks, what round they use, what sight they have on their AR or M4 or whatever. So it’s a very gear-heavy world. So the two things I think of are knives and compasses. Those are the sort of touchstones of the military guy and the adventure guy.

Is that what inspired DPx?

I was bugged for ten years by a friend to design a survival knife. And I just put it off for a long time, like ten years. You know, I had my own TV series and didn’t develop any products. I just was very against that whole idea of exploiting all the war zones and rebel groups and the dead people. And over time I thought, “You know, I can’t find a decent goddamn knife! I should design one!” So I sat down, and I designed this knife. It’s quite small. It was called the HEST (Hostile Environment Survival Tool), made out of spring steel, tempered. And it was a very handy, very useful knife! And it sold like crazy!

Carry tip: stuff filthy old clothes into your pack and around your valuables to deter snooping customs officials.

Now, what knife do you use now personally? What’s your go-to DPx?

I use an Aculus, which is a solid piece of titanium with such a thin gentleman’s blade. If you Google “Aculus,” you’ll see what it looks like. It’s a very elegant blade. But our knives are also designed to be used in non-lethal applications. So when you put it in your fist – you know, it’s kind of like brass knuckles with a skull crusher on the end… I don’t endorse the use of knives or weapons for anything violent. But if you had to protect yourself, you’re much better using a blunt instrument and not going to jail for 20 years than using a knife and potentially harming or killing an assailant.

What else do you carry?

I have a very strange collection of things. I believe you must always carry a transit. I believe you should always carry lots of cash. You can always pay somebody to tell you where the nearest exit is. I also bring a cheap watch that I can give away. I always like to give things away. I always like to carry a small book that has interesting things from another era, ’cause you know, when you get stuck somewhere, you can crack open a book, and I’ve sort of been leaning on my iPad for that function. But if you go on Amazon, there are all these amazing old free books written in the 1800s and 1700s about adventure. And it’s fascinating to read these very, very old tales of places that you go to.

Rad. Anything else?

I carry hot sauce, which people think is weird. Most spoiled food, when it gets pretty miserable, can be made edible by hot sauce. Like I said, I carry a transit rather than a compass, but it’s just a simple little way to find out where you are and where you’re going. I think that the new sort of small iPad or big iPhones are actually essential now because of these very cool apps. Most people don’t realize that the new iPhone not only has a GPS and a compass, but also a barometer. So it now becomes the singular scientific measuring tool. It’s not very accurate, but you can use it in a pinch. And you can also read books, play music, and take pictures. It’s everything in one. And unfortunately, as soon as you drop it in a stream, it’s useless. It’s got a lot of uses that most people wouldn’t really think about in an exploratory way.

“I believe you must always carry a transit. I believe you should always carry lots of cash. You can always pay somebody to tell you where the nearest exit is. I also bring a cheap watch that I can give away. I always like to give things away.”

I also have one of these little satellite burst tracking systems, it’s called a DeLorme inReach, which I don’t use the tracking part, but it allows me to send texts. And then when you send the text, it shows you exactly where the text came from on the map.

How about carry challenges? Anything tricky in your line of work?

Yes, of course. One of my problems is I can’t carry a lot of stuff, because if I get arrested, I can’t carry names of people. So usually I clean my phone off. I have a clean phone and I have a clean passport. I don’t carry a lot of documents and things like that. Technically, travel is hindered by the more stuff you carry, the more difficult it is to move around. And unfortunately, everything now is digital and linked to some electronic or Internet connection. But when you do slow journalism, when you’re really trying to understand something, if you read the South Sudan article I did, one of the things that fascinated me was I was missing the mythological context of the people who were killing other people.Yet, they relied on a prophet to dictate what time to attack a certain village and a certain place. And I was thinking of it in electronic times, like a geolocation and a physical time, and I thought, “No, these people are moved by some spiritual linkage which is not electronics; it’s not linked to anything that we would have and plug into the wall.” So, one of the things that’s interesting is when you get into these remote areas and talk to these groups, they have very, very strong connections to some kind of mystic driver, as opposed to technology.

And a funny thing is when I met with Dr. Riek Machar, a rebel leader, he couldn’t get his iPhone to work, and so we had to call customer service from the secret rebel camp to link up his sat phone. And this is at the same time that he’s consulting the mystics on what time to attack this village, by killing a cow. This is the modern world we live in.

That is so intriguing. And kind of twisted too. How about packs? What do you sling on your adventures?

When I travelled, I realized that customs guys would look for stuff in your packs. They would pull everything out of them and say, “What’s this?” So first I started using a Becker Patrol pack, which was designed by a friend of mine. It’s got this secret spot, and it has a bunch of pockets on the outside. And I would stick one of the most foul-smelling underwear and socks and dirty laundry on the inside, and they would just get frustrated rummaging – “Just leave!” – so they wouldn’t touch my money or my other stuff.

Eagle Industries Becker Patrol Pack

And then I moved up to a jumpable Navy Seal backpack, which has big grommets and two giant straps, ’cause basically when you jump out of an aircraft you drop your pack before you hit the ground. But it’s a big, wide heavy pack.

And then I moved up to a Colombian Commando Pack, which I use. And what I find is missing from the pack designers that I see today is the idea of, “You’re using this to travel, what do you need to think about?” Forget your iPad, forget convenience. How do you hide stuff in there? So when people rummage through your bag, well they find it. Now, the packs I have, I’ve carried knives for months without realizing that those knives were in there. Like, literally going back and forth through TSAs, screenings, over and over and over again, and nobody has found everything, because there are certain ways to pack your pack, that you won’t find these little secret inner pockets with other metal things next to them. And you see I’ve invented the Danger Tag, my little patented carry-on emergency knife, which looks like a luggage tag. So, very little thinking is going into the worst case or bad case scenarios for how you deal with luggage. And that includes flammability, people taking a razor blade and cutting right through your bag to get to stuff. That means zippers breaking, that kind of stuff. So I’m not really impressed with the new generation of bags, which tends to be overly mil-spec, which means tons of straps and buckles and crap that doesn’t do anything. Or, the sort of very light, flimsy Osprey high-tech bits and pieces all strung together kind of pack.

“…what I find is missing from the pack designers that I see today is the idea of, “You’re using this to travel, what do you need to think about?” Forget your iPad, forget convenience. How do you hide stuff in there?”

The best pack was the Becker Pack with the UN flour bag. They make a hundred-pound or a hundred-kilo flour bag. So I would take my Becker Pack, which was carry-on size, and I would take a UN flour sack and then shove my pack into this dirty, filthy old sack, and nobody would bother looking at it, because it’s this grubby thing. So my point is that I’d like to see a move towards more intelligent luggage – so if any luggage designers want to call me…and move away from this sort of prissy purple steal-my-shit look that seems to be going around, we can do something together.

Oh, another thing too is the butt bag – you know, the fanny pack or whatever they call it.

Yes. Let’s talk about that…

I used to carry two fanny packs. So when I ran in combat I had all my stuff with me. But when I got inspected, I would move my back to the bag, and they would want to test that, so I would flip it around, and they didn’t realize that they only checked one side. So all my money was in the back one. And when they would say “Let’s see it,” I would rotate it around.

And the other thing is, when you get robbed, people will think that all your stuff is in your fanny pack. So I always carry a fake wallet with Ugandan money or whatever, that if somebody wanted to take your stuff or ask for your stuff, you would have this pretty functional wallet with expired credit cards, and then they’re good with that.

That’s genius!

So the fanny pack is the thing that people focus on, because they assume that all your valuables are in there.

Yeah, totally!

It may be a fashion faux pas but it may save the bacon one day.

Anyhow, so the point is you can buy any kind of bag: camera bags; trendy, expensive leather, whatever. But rarely do I see designers make luggage for people who travel in war zones.

Hopefully this interview kicks something off. We’d be stoked to see a ‘war zone’ specific pack!!

That was one awesome ride, Robert. Big thanks for chatting to us!

My pleasure.

Bye bye.

*Oh, and check out DPxGear’s new EDC knife Kickstarter that has gone ballistic!

Carry Awards

Carry Awards Insights

Insights Liking

Liking Projects

Projects Interviews

Interviews