Insights

Here’s a test you can do right now. Look down at your jacket. Your jeans. Your bag. Find a zipper—any zipper—and check the pull tab. Three letters. YKK.

Try another. Your backpack. Your hoodie. Your tent, if you’ve got one nearby. YKK.

It’s everywhere. And once you start noticing, you can’t stop. It’s like discovering a secret language written into the fabric of modern life.

Those three letters stand for Yoshida Kōgyō Kabushikigaisha—Yoshida Manufacturing Corporation. And they represent one of the most successful, least-known companies in the world.

YKK produces roughly half of all zippers made globally. Seven billion zippers a year. In some markets—Japan, for instance—their share approaches 90%. If you’ve ever zipped anything, there’s a better-than-even chance it was theirs.

But here’s what fascinates me: they didn’t get there through aggressive expansion or undercutting competitors. They got there by being better. By obsessing over a component most people never think about. By treating the humble zipper not as a commodity, but as a craft.

And after ninety years of that obsession, they’re not resting. They’re constantly evolving—pushing the zipper into territory it’s never been before.

Let me tell you the story.

TADAO YOSHIDA AND THE CYCLE OF GOODNESS

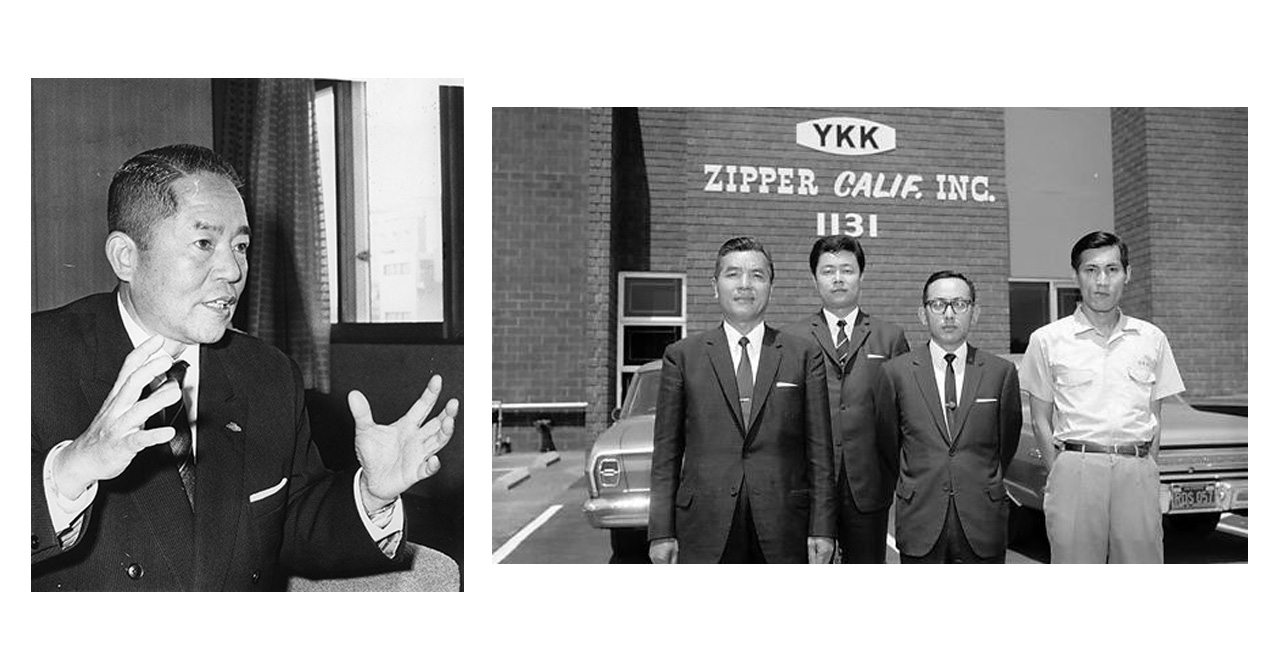

The story begins in 1934, in Tokyo, with a man named Tadao Yoshida.

Yoshida wasn’t an engineer. He wasn’t from a manufacturing family. He was the son of a shopkeeper who’d worked odd jobs—sales, trading, small business ventures—before deciding, at age 31, to start a zipper company.

This was not an obvious choice. Japan in 1934 was industrializing rapidly, but zipper manufacturing was dominated by American and European companies. The technology was foreign. The equipment was expensive. The market was already crowded.

But Yoshida had a philosophy that would define everything YKK became. He called it the “Cycle of Goodness”: “No one prospers unless they render benefit to others.”

It sounds almost naïve. A business platitude. But Yoshida meant it literally. He believed that if YKK made a product that genuinely benefited customers—that was more reliable, more durable, more consistent than the competition—then success would follow naturally.

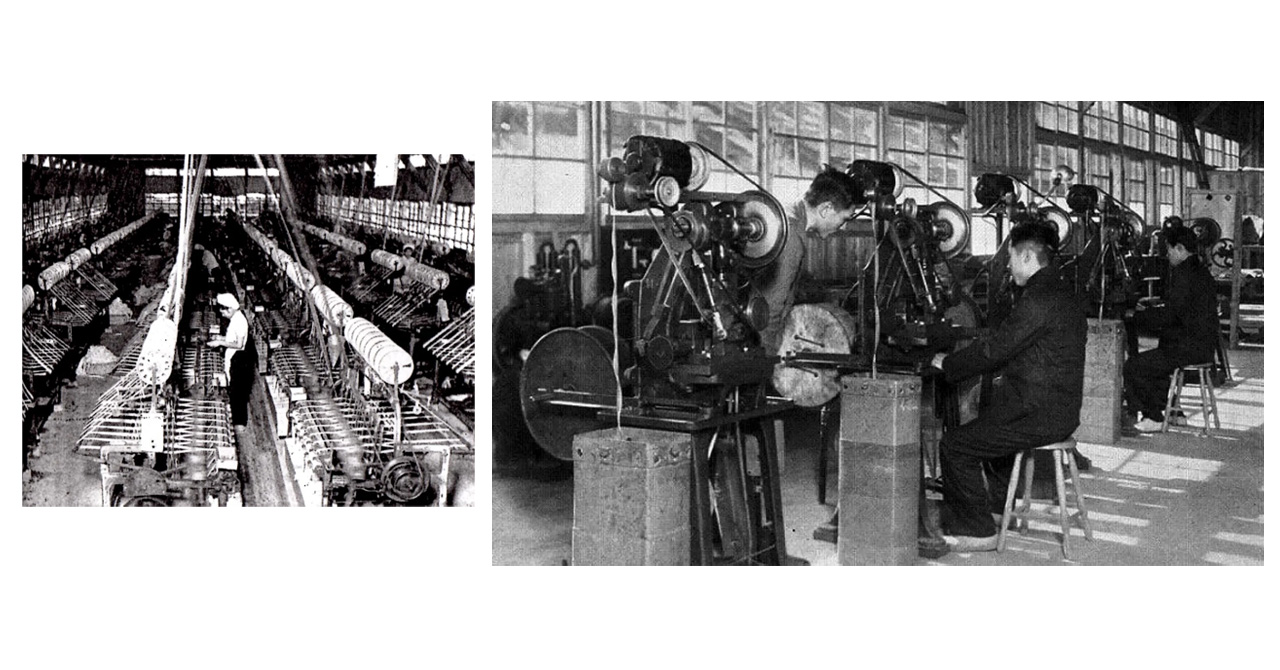

He started small. A single factory in Tokyo’s Nihonbashi district. A handful of employees. Yoshida himself worked the machines, learning every step of the manufacturing process. He didn’t just want to make zippers. He wanted to understand them—the metallurgy, the tolerances, the failure modes.

And he had a rule: YKK would control the entire supply chain.

This was unusual. Most zipper manufacturers bought components—metal wire, fabric tape, sliders—from suppliers and assembled them. Yoshida insisted on making everything in-house. He built wire-drawing machines. He wove his own tape. He cast his own sliders.

Why? Because he couldn’t guarantee quality otherwise. If a zipper failed, he wanted to know exactly why—which material, which process, which tolerance had been compromised.

It was obsessive. It was expensive. And it worked.

THE WAR YEARS: SURVIVAL AND REINVENTION

Then came World War II.

By 1941, YKK had grown into a mid-sized manufacturer with several factories. But wartime Japan had little use for civilian zippers. The government redirected industrial capacity toward military production—uniforms, equipment, munitions.

YKK pivoted. They made zippers for military gear, but also expanded into metal components—buckles, fasteners, small parts for aircraft and vehicles. It wasn’t glamorous, but it kept the company alive.

The war devastated Japan’s industrial base. By 1945, much of Tokyo was in ruins. YKK’s factories were damaged. Supply chains collapsed. The economy was in freefall.

But Yoshida saw an opportunity.

Post-war Japan needed everything. Clothing. Bags. Tents. Rebuilding infrastructure meant rebuilding the objects of daily life. And all of those objects needed fasteners.

YKK retooled. They rebuilt their factories with newer, more efficient machinery—much of it designed in-house, because imported equipment was prohibitively expensive. They trained workers in precision manufacturing techniques. They focused on consistency and quality control, knowing that in a resource-scarce economy, a reliable product would win.

By the early 1950s, YKK was the dominant zipper manufacturer in Japan.

But Yoshida wasn’t satisfied with domestic success. He wanted to go global.

BUILDING A VERTICAL EMPIRE

In 1960, YKK opened its first overseas factory in New Zealand. Then Australia. Then the United States, Europe, Southeast Asia.

This wasn’t typical outsourcing. YKK didn’t just build assembly plants. They built fully integrated manufacturing facilities—wire production, weaving, dyeing, slider casting, assembly, all under one roof.

Why? The same reason Yoshida insisted on vertical integration in the 1930s: control.

If YKK made zippers in the U.S. using American-made wire and locally-woven tape, they could guarantee the same quality standards as their Japanese factories. No variability. No supply chain dependencies. No compromises.

It was capital-intensive. It was slow. But it created something unprecedented: a global manufacturing network that could produce identical products anywhere in the world.

And it gave YKK an unbeatable advantage: consistency.

A garment brand could source zippers from YKK’s factory in Bangladesh, Vietnam, or Ohio, and they’d be interchangeable. Same specs. Same tolerances. Same reliability. That’s rare in manufacturing, and it’s incredibly valuable for brands managing global supply chains.

By the 1970s, YKK was the largest zipper manufacturer in the world. By the 1990s, they held roughly 50% of the global market.

They’ve held that position ever since.

Let’s be clear: YKK isn’t alone. There are competitors. RiRi. Coats, which owns Opti and other brands, competes in the market. SBS Zippers, KCC Zipper, and various regional manufacturers all have their share. In some markets, particularly China, local producers have significant presence.

But YKK dominates the premium segment. If you’re making high-quality outdoor gear, technical apparel, or luggage, you almost certainly use YKK. Their reputation for consistency and reliability is unmatched.

YKK invests heavily in R&D—unusual for a fastener company. They hold thousands of patents. They run materials science labs. They test zippers under conditions most manufacturers would never consider: extreme cold, saltwater exposure, UV degradation, tens of thousands of open/close cycles.

They’re not just making zippers. They’re treating the zipper as an engineering problem worth solving.

CONSTANTLY EVOLVING: RETHINKING THE ZIPPER

For most of YKK’s history, innovation meant incremental improvement. Better corrosion resistance. Smoother sliders. More durable coils.

But in the past few years, something’s shifted.

YKK isn’t just refining the zipper anymore. They’re rethinking it entirely.

After ninety years of mastering the fundamentals, they’re finally asking: what else could a zipper be?

Let me show you three examples.

AIRYSTRING

Look at a zipper. Any zipper. Notice those fabric strips running along both sides of the teeth? That’s the tape—the woven material that’s been part of every zipper since Gideon Sundback invented the modern design in 1913.

AiryString removes it entirely.

At first glance, it looks like a normal zipper. Then you realize what’s missing. No tape. Just teeth, slider, and the garment fabric itself.

That absence transforms everything.

Without the woven fabric tape, the AiryString is lighter, sleeker, and far more flexible. But more importantly, it sinks into the garment instead of sitting on top of it. It’s a fastening system that becomes part of the fabric structure rather than an add-on component.

“We wanted to address the challenges involved in zipper sewing,” says Makoto Nishizaki, YKK’s vice president of Application Development. The idea grew from a collaboration with JUKI Corporation, a leader in industrial sewing machines. Together, they reconsidered how a zipper could be made and how it could merge more seamlessly with fabric.

The partnership began in 2017 and made its public debut at a trade show in 2022. That timeline tells you something about how YKK operates—they play the long game.

The engineering challenge was immense. Those fabric strips aren’t just decorative. They give a zipper its structure. They provide the surface tailors sew through. They distribute stress along the closure line. Remove them, and you have to rethink everything.

The teeth were redesigned. The manufacturing process rewritten. New machinery developed to attach the closure directly to garments. “The absence of the tape posed various production challenges,” Nishizaki says. “We had to develop new manufacturing equipment and a dedicated sewing machine for integration.”

The result is a zipper that moves more naturally with the body. That lies flatter. That feels less mechanical. Garments made with AiryString have a softer, slicker glide—that satisfying pull that separates a well-made jacket from a cheap one. “In terms of usability, AiryString offers much smoother operability,” Nishizaki says.

But it’s not just about feel. By removing the tape, YKK trims both material and labor. Less fabric. Less dye. Fewer sewing passes. “It contributes to reducing work in customers’ sewing processes,” Nishizaki says. “It also reduces fiber use and water consumption in the dyeing process, lowering CO₂ emissions.”

YKK offers a 100% recycled-material version of AiryString and claims measurable cuts to greenhouse gas emissions and water usage. When you make billions of zippers a year, small efficiencies ripple globally.

Descente Japan prototyped AiryString in 2022. The North Face selected it for their new Summit Series Advanced Mountain Kit. Smaller brands like Earthletica, an eco-conscious performance label, have tested it, describing the zipper as “soft, flexible, and almost silent.”

Modern fabrics—featherlight nylons, stretch blends, technical materials—have evolved faster than zippers. The old design, with its woven borders and stiff seams, feels out of sync with what surrounds it. AiryString catches up. It’s a zipper designed for fabrics that didn’t exist when the zipper was invented.

The product is in production now, rolling out to commercial partners throughout 2025.

THE SELF-PROPELLED ZIPPER

This one sounds like a joke. A zipper that zips itself.

But it’s real, and it’s surprisingly clever.

YKK demonstrated a prototype at trade shows: a zipper with a small motor embedded in the slider. Press a button, and the slider glides up or down the teeth automatically.

Why would anyone need this?

The obvious answer is accessibility. For people with limited hand mobility, arthritis, or motor control issues, zipping a large tent can be genuinely difficult. A self-propelled zipper removes that barrier.

But there are other applications. Operating a zipper with thick gloves in cold-weather gear is frustrating. A motorized slider eliminates fumbling. Medical garments like compression suits or post-surgical wear—anything where precise closure matters but manual dexterity is compromised—could benefit. In high-stakes environments like spacesuits or hazmat gear, a reliable, one-button closure could be a safety feature.

The engineering is fascinating. The motor is tiny—powered by a small battery embedded in the slider or connected via a thin wire. The mechanism has to be strong enough to pull the slider under load, but light enough not to add significant weight. And it has to be waterproof, durable, and fail-safe. If the motor dies, you can still operate it manually.

Is it overkill for most applications? Absolutely.

This remains a prototype and concept. It’s not yet in commercial production, but the technology exists and works.

THE REVIVED COLLECTION

Here’s the most important innovation—and it’s not a single product. It’s a philosophy.

The YKK Revived Collection is a series of repair-focused components designed to keep zippers functional and maximize a product’s lifecycle. The goal is simple but radical: the zipper should never be the reason a product is thrown away.

YKK has developed three main components in the Revived series, each targeting a specific failure mode. Together, they represent a fundamental shift in how YKK thinks about their products—not just as components to be manufactured and sold, but as systems to be maintained and repaired.

REVIVED TOP STOP: THE SLIDER YOU CAN REMOVE

Traditional center-front zippers—the kind you find on jackets and hoodies—have a problem. When the slider breaks or the pull tab snaps off, you’re stuck. The standard repair requires cutting off the top stop, that metal or plastic piece that keeps the slider from flying off the end, and replacing the entire slider. It’s destructive, time-consuming, and often requires specialized tools.

The Revived Top Stop changes that. It looks like a standard top stop, but with a zigzag groove pattern cut through it. That channel allows you to orient the slider through the stop and derail it, removing it without cutting anything.

Need to replace a broken pull tab? Just guide the slider through the zigzag channel, swap it out, and reverse the process to reinstall it. No seam ripper. No pliers. No destruction.

The zigzag design is intentional. It prevents unintended removal. You have to deliberately maneuver the slider through the channel, so it won’t accidentally come off during normal use.

The product works on standard open-end zippers, removable open-end, and two-way open-end zippers. It’s currently available for size 5 Vislon, YKK’s molded plastic tooth zipper, with plans to expand to size 5 reverse coil and AquaGuard coil zippers.

There are some limitations. It’s not recommended for kids’ garments because if the slider does come off, it poses a choking hazard. And you have to spec it in from the beginning—it’s not something you can retrofit onto an existing zipper.

But the impact is clear. A broken pull tab shouldn’t mean a dead jacket. This makes slider replacement a five-minute fix instead of a forty-dollar tailor visit.

REVIVED REPLACEMENT SLIDER: THE TWO-PART FIX

Pocket zippers and accessory zippers—chest pockets, hand pockets, ventilation zips—are different from center-front zippers. They’re closed-end or chain-in-slider designs. The slider can’t be removed from the ends because there’s no opening.

When the slider breaks on one of these, the traditional fix is either replacing the entire zipper or cutting into the fabric to access the chain. Both are destructive and labor-intensive.

The Revived Replacement Slider solves this with a two-component design. There’s a top portion with the pull tab, slider crown, and upper slider body. The bottom portion contains the sliding surfaces that engage the zipper teeth. The two parts snap together.

To replace a broken slider, you separate the old one, remove it, and snap a new one onto the zipper chain without cutting or sewing anything.

The product is currently available for size 3 reverse coil zippers, the most common pocket zipper size, in both PU-laminated and AquaGuard water-repellent versions. Free sliders are available now; double-pull sliders are coming later in 2025. YKK plans to expand to size 5 reverse coil, common for larger pockets and vents, and eventually other sizes and chain types.

There are some trade-offs. The bottom component, the sliding surfaces, is only available in silver or C5 plating. This ensures consistent thickness and snap-fit strength across all sliders. Because it’s two parts instead of one solid piece, it’s weaker than a single die-cast slider in some strength tests. It’s still strong enough for pocket and accessory use, but not recommended for high-stress applications.

It’s also not recommended for kids’ garments because of choking hazard concerns, and the pull tabs don’t meet tab-twist safety standards. Custom pull tab shapes are possible but have tighter design parameters to avoid interlocking during manufacturing.

But the core innovation remains powerful. Pocket zippers fail constantly—snagged pull tabs, broken sliders. This turns a zipper replacement from a destructive repair into a snap-on fix.

REVIVED REPLACEMENT PULLER: THE BAG ZIPPER FIX

Luggage and bags use a different zipper type: racket coil zippers, typically size 8. These are heavy-duty, with large coil teeth and robust sliders.

The most common failure is broken or missing pull tabs. The slider body is fine, but the pull tab snaps off or gets torn away.

The traditional fix is either replacing the entire zipper, which is expensive and time-consuming, or attaching a makeshift pull—a carabiner, a zip tie, something you can grab onto. Neither is ideal.

The Revived Replacement Puller is a pull tab designed to snap on and off the slider without tools. It has an L-shaped channel on both the front and back, with a small TPU-injected component on the front side. The slider crown has a corresponding narrow channel on top and a wider channel on the bottom.

To replace a broken pull tab, you orient the new pull tab with the narrower TPU side facing the top of the slider. You slide the L-channel over the slider crown until it clicks into place. Done.

The asymmetric design—narrow top, wider bottom—ensures you install it in the correct orientation. No guessing. No special tools.

The product is currently available for size 8 racket coil zippers, the most common luggage and bag zipper. It can be developed for size 5 and size 10 RC zippers on request. Custom pull tab shapes are possible. You can add logos and change the shape, as long as the L-channel and TPU component remain functional.

There are limitations. You have to spec it in from the beginning. This isn’t something you can retrofit onto an existing RC zipper because the slider crown needs the corresponding channel design. It’s also limited to plating finishes, not enamel. Enamel coatings are thicker and can create too much resistance when removing and reinstalling the pull tab.

But the impact is significant. Luggage zippers are long, expensive, and integrated into complex bag structures. A broken pull tab shouldn’t mean replacing a fifty-dollar zipper. This makes it a thirty-second fix.

REPAIR AS INFRASTRUCTURE

Here’s what ties the Revived Collection together: YKK is building repair infrastructure.

They’re not just selling replacement parts. They’re designing zippers to be repairable from the start, and they’re working with brands, warranty centers, third-party repair shops, and even consumers to make those repairs accessible.

“We’re targeting this for warranty and quality centers, third-party repair centers, potentially in-store retail repairs, and eventually consumer repairs,” says John Holiday, YKK’s Senior Product Development Manager. “We want to make sure the fastener or the zipper is not the reason a product is no longer in use or why it needs to be warrantied.”

That’s a shift. Traditionally, YKK sells zippers to manufacturers in bulk—cut zippers or chain-and-slider assemblies. The Revived components are sold as standalone parts, which means YKK is rethinking its distribution model to make replacement parts available outside traditional manufacturing channels.

I started this piece with a test: look at your zippers. Three letters. YKK.

Now you know why they’re there. Not because of aggressive marketing or locking out competitors. Because a man in 1934 Tokyo decided that if you make something genuinely better—more reliable, more consistent, more thoughtful—success follows naturally.

Ninety years later, YKK still operates on that philosophy. They’re still privately held. Still vertically integrated. Still obsessing over a component most people never think about.

And it looks like they’re not done. They’re constantly evolving.

Carry Awards

Carry Awards Insights

Insights Liking

Liking Projects

Projects Interviews

Interviews

One thought on “The Company That Zips the Globe | YKK’s Ninety-Year Obsession”

Comments are closed.