Brands

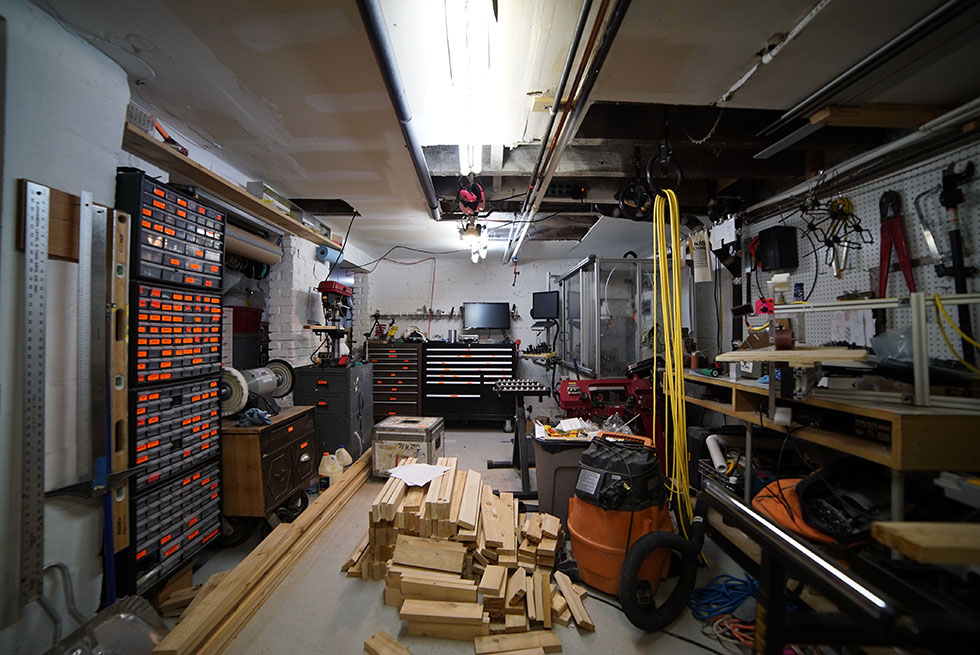

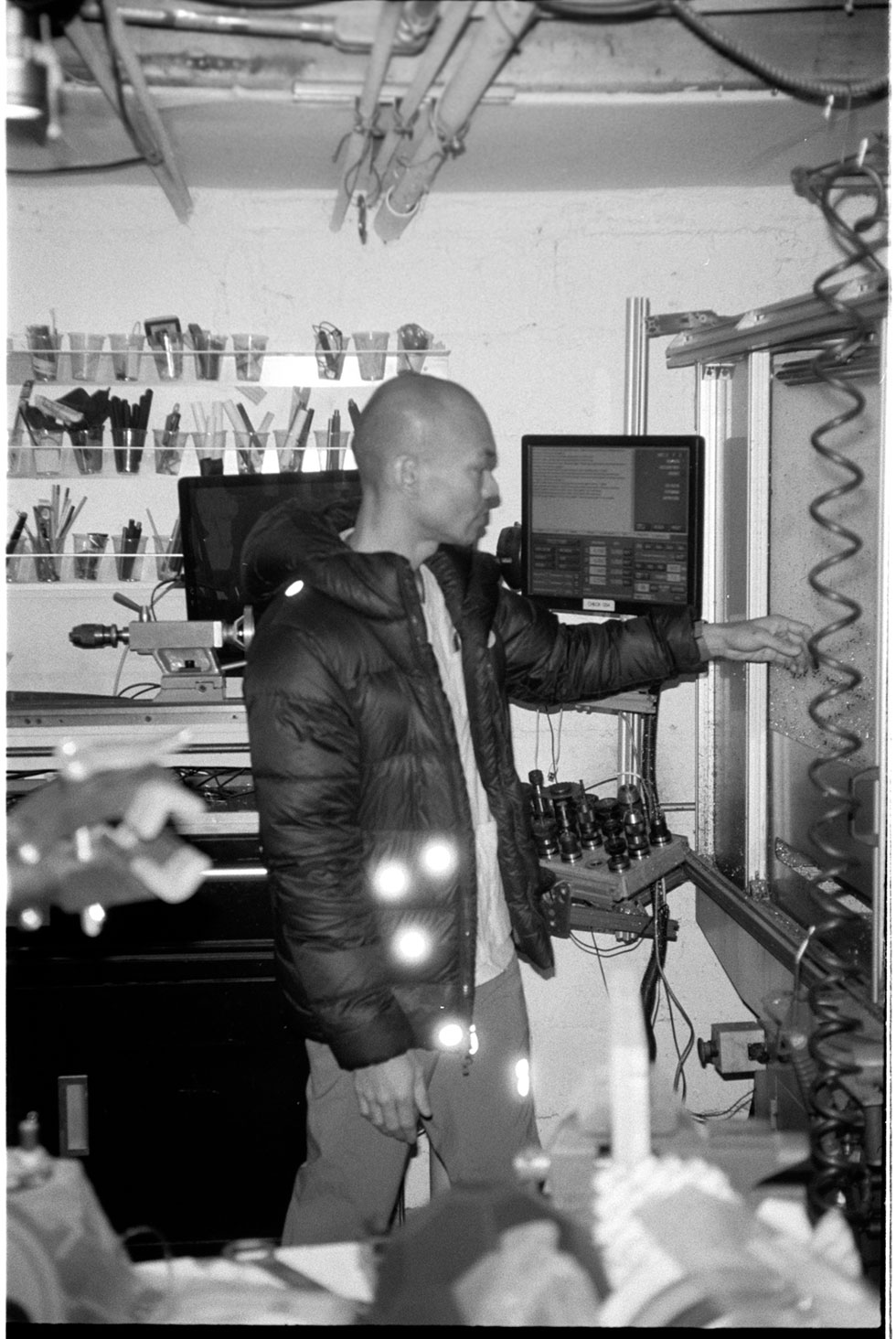

Somewhere in Brooklyn, there’s a design studio without a sign. No storefront. No showroom. Just a brownstone buried in two feet of snow. In the basement Che-Wei Wang and Taylor Levy make things with their hands.

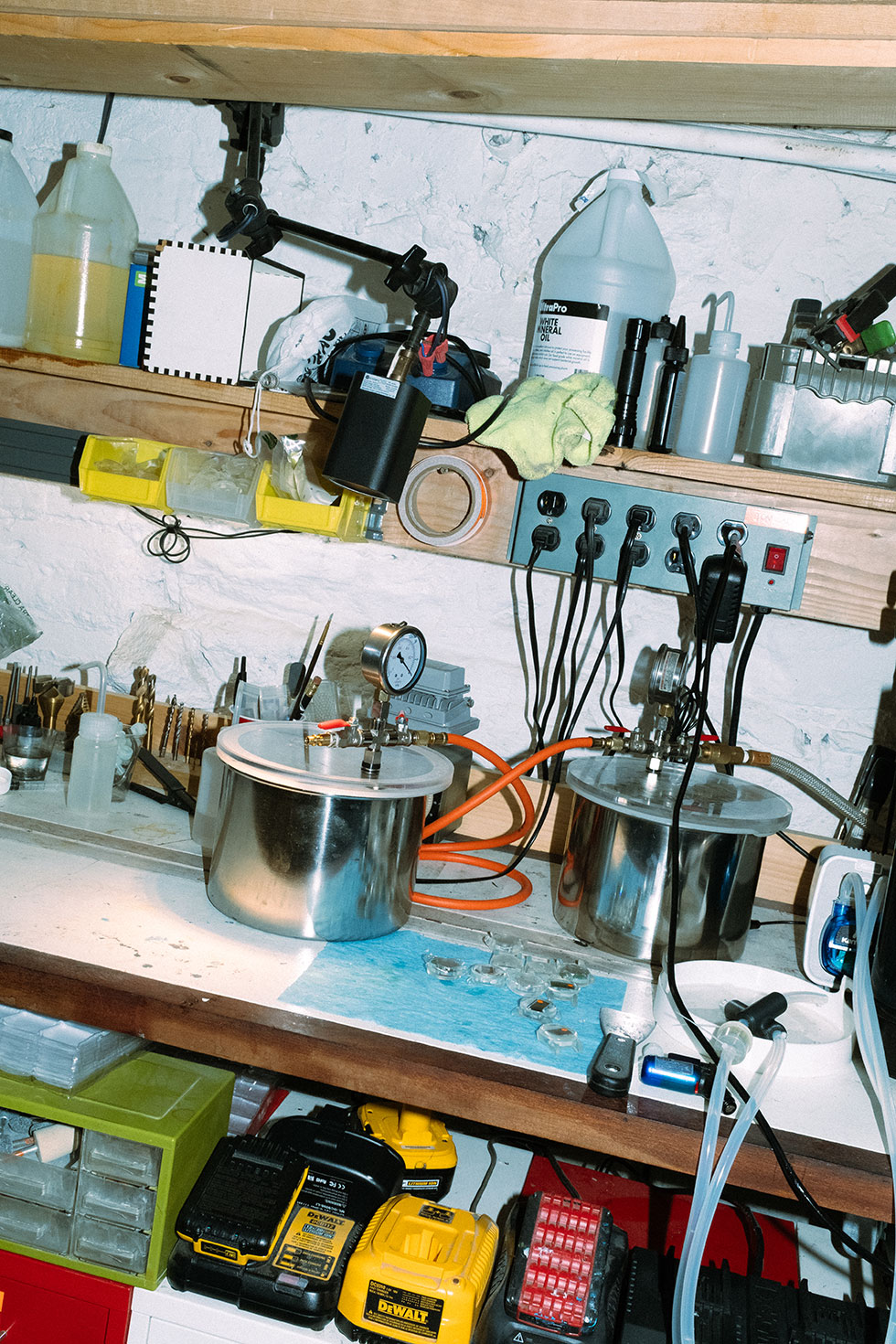

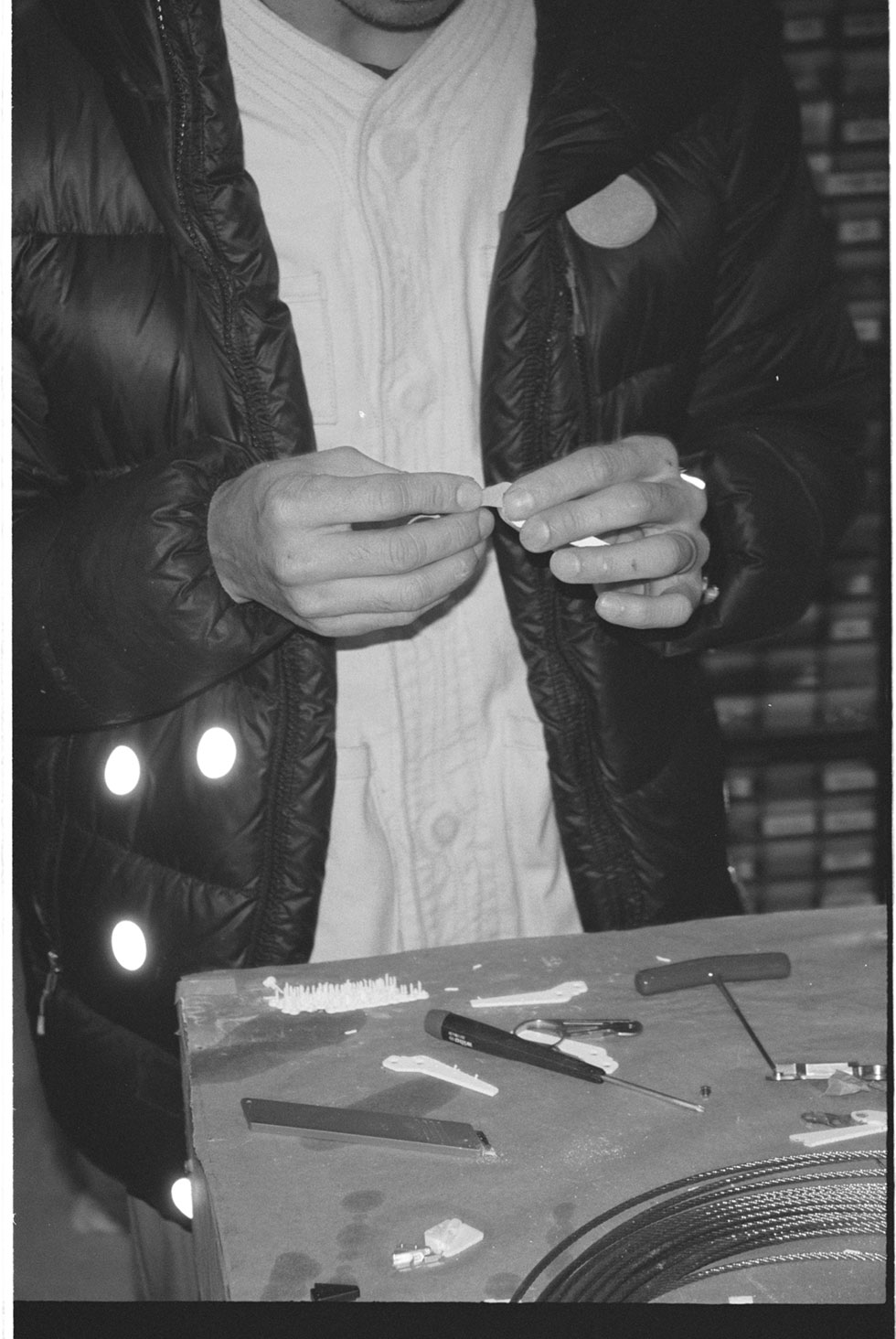

Around them, the workshop hums. 3D printers churn out prototypes along one wall. Nearby a retrofitted lathe. A homemade laser cutter. An injection molding machine. A Tormach 700 CNC behind transparent glass. Tools everywhere—chop saws, sanders, polishing wheels—all mounted on handmade buggies.

Upstairs there’s a photography space. An industrial sewing machine. An electronics bench. Across the yard, through the snow, another building. They assemble there. They pack. They ship.

And they make things that bring them joy. That’s the only rule.

Let me explain.

This workspace belongs to Che-Wei Wang and Taylor Levy, a husband-and-wife duo who think differently about design and the objects we carry—not in the way that phrase is usually deployed in marketing copy, but in a more fundamental sense. They question the very premise of what a tool should do, how long it should last, and whether making you happy might be a more honest metric than making you productive.

But to understand why they create this way, you need to know where they came from.

The Typewriter and The Beatles

Che-Wei Wang was nine years old when his father’s motorized typewriter broke. Most parents would have tossed it or sent it for repair. His father did something unusual: he gave his son permission to take it apart.

In a 2022 interview, Che-Wei recalled it as his “first memory of having the opportunity to take something relatively complex and expensive” with his parents’ blessing. He took it apart. And he fixed it.

That moment—cracking open the casing, seeing the mechanical guts, understanding the puzzle—ignited an obsession. He’s described how, since that moment, he never lost the desire to take things apart, both literally and conceptually. His default response to seeing anything became: “I think I can make a better version of that.”

Growing up in Yokohama, Japan, Che-Wei spent his high school years walking through Tokyo Hands—a legendary store—five days a week on his way home from school. He was fascinated with all of the beautiful objects inside.

“I remember this one moment where they have this whole DIY section where they sell every material in beautiful blocks,” he says. “I was gonna buy this chunk of wood, I’m gonna carve it into this thing. I don’t know, I think I was like 10 years old trying to figure out how to carve a piece of wood. I remember that frustration quite a bit because nobody around me knew how to make things.”

It’s what Ira Glass famously calls “the gap”—that brutal period where your taste is good, but your skills haven’t caught up. Che-Wei lived in that gap for years, surrounded by objects he could appreciate but not yet create.

Meanwhile, across the Pacific in Montreal, Taylor Levy was grappling with a different kind of gap. She viewed truly creative forces—The Beatles, great filmmakers—as almost inhuman, as if they were a different species with access to magic she didn’t possess.

Then the illusion shattered.

She came to realize that everyone are really just people—that everyone has the capacity for creative work if they have the desire. That democratized view of creativity—combined with a background in both film and computer science—gave Taylor a rare fluidity between the virtual and physical worlds. Where most people see a massive psychological wall between the screen and the workshop, Taylor saw continuity. Making things virtually and making things physically, she’s said, were never that different in her head.

The breakthrough for Che-Wei came when he broke his knee senior year of high school and was forced off the sports field into an art room. There, a supportive teacher gave him what he’d been given once before: permission. Gallons of wax. Silver solder. Raw materials and unstructured time. No specific assignment. Just: make something.

He never looked back. Architecture school at Pratt in Brooklyn. Then grad school at NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program—a place where you learn just enough to make the thing you want to make, in whatever unsafe way gets you there fastest. They all learned together in one big room, side by side, working together, sharing ideas.

Taylor arrived at the same program after studying film and computer science at a liberal arts school. She’d already started a small business making custom iPod sleeves in the early 2000s. She’d done the whole thing—manufacturing in small batches, building a website, pitching to stores. Then she got bored and moved on. The pattern was set: start projects, figure them out.

At ITP, they met. They started collaborating before they started dating. Their first paid project together was designing custom software for massive projection screens at Obama’s 2008 inaugural ball—a compressed, intense build over winter break that established their working rhythm. From there the journey was software, interactive art, but making objects with their hands and machines is what has reverberated most.

The Anti-Market Research Manifesto

CW&T operates according to principles most business schools would likely shun.

Principle One: “Buy Lots of Lottery Tickets”

Borrowed from their friend Darius Kazmi, this philosophy rejects the idea that you can predict what will resonate with an audience. As Che-Wei has explained publicly, they’ve learned there’s often zero correlation between how much they like something—or how much time and money they spend on it—and whether others will appreciate it. The only strategy that works is to just keep trying things.

Principle Two: “Make What You Want”

They explicitly reject traditional industrial design methodologies—focus groups, user personas, market research. In a recent podcast interview, Che-Wei explained their approach: they don’t have the resources for market research, and more importantly, they’re not interested in it. They design for one or two people, and those people are usually themselves.

His advice to other designers, shared publicly: Be your own best critic and user tester. Make stuff you want. Don’t worry about what millions of other people want, because designing for mass appeal often means nobody—including you—actually wants the thing.

It’s the opposite of the Kickstarter backpack with 40 features. CW&T’s products are suggestions, not solutions. They’re not claiming to make the best version of anything. They’re asking: What if we thought about this differently?

When their first Kickstarter campaign blew up beyond expectations, the lesson was clear: if they were just really honest about what they wanted and executed on that without cutting corners, they’d find other people who felt the same way. The world is big enough. They don’t need to sell to a million people. They just need to find the right people.

Time Since Launch

When asked about his favorite project, Che-Wei doesn’t hesitate: Time Since Launch.

It’s a single-function device that does nothing but count up from the moment you “launch” it by pulling a pin. It’s engineered to run for decades—potentially centuries—on standard AA batteries. There are no buttons to reset it. No app. No connectivity. Just a relentless, precise count of elapsed time.

The inspiration came from astronaut John Glenn, who wore a stopwatch in space rather than a traditional watch. As Che-Wei has explained, on Earth it matters what time it is, but in space, what matters is how long it’s been since you launched. In space, GMT is meaningless. What matters is mission time—time since the specific moment your journey began.

In discussing the project publicly, Che-Wei described it as empowering—a way to regain ownership over time, which he views as both top-down and oppressive. Time Since Launch allows users to mark a specific moment—a birth, a marriage, a death, a decision—and claim it as their personal epoch. It’s a rebellion against synchronized global time.

The engineering reality, however, is humbling. The idea existed for years before their neighbor, electronics “wizard” Josh Levine, helped them engineer ultra-low-power circuits that could actually deliver on the promise. Even then, getting component manufacturers to guarantee longevity was nearly impossible.

The Solid State Watch

Taylor’s favorite project is even stranger: the Solid State Watch.

Take a ubiquitous Casio F-91W digital watch—the $20 icon that runs for 15 years on a single battery. Set it to your time zone. Then permanently cast the entire thing inside a solid block of crystal-clear resin. You lose access to the buttons. The backlight. The alarm. The ability to ever change it.

In a podcast interview, Taylor described it as “a hard ask”—they’re essentially asking people to pay more money for something they’re making by hand that’s objectively worse than what you can buy at the store. But there’s a story they want to surface that they believe is meaningful.

That story is about the incredible engineering of a cheap watch that outlasts most smartphones by a decade, contrasted with our modern, fragile, dependent technology. By sealing it, you consent to living with its eventual drift in accuracy and its ugly death when the battery fades. You elevate your awareness of the object’s lifespan.

Taylor has offered a crucial nuance to the design principle that “good design is long-lasting.” She’s said she doesn’t really go for long-lasting design—rather, things should last how long they should last for.

The distinction matters. Their machined titanium pens should last lifetimes. The Solid State Watch is designed to become obsolete. What matters to Taylor is transparency when the transaction happens.

Optimizing for Joy, Not Utility

In a world obsessed with specs—titanium grade, lumen count, blade steel—CW&T proposes a radically different metric for evaluating gear:

Does this object make you feel happier than you did before you used it?

Taylor has described how a great tool should make you feel happier than before you used it. She wears the Solid State Watch every single day, and it makes her just a little bit happy every morning.

It’s about emotion. Taylor reveals a project in the works: a phone for their child shaped like a banana with only one button that calls her.

She thinks it won’t be the best phone, but it’ll bring joy—and crucially, it won’t do the inverse, a subtle dig at smartphones that, despite their capabilities, often make us feel worse.

CW&T believes that in the physical tool world, objects really want to just do one thing really well. Taylor has been particularly blunt about “smart” devices in past interviews: there’s no reason to make your toothbrush Wi-Fi enabled just because you can embed chips in things.

“I’m very sensitive to bad stuff,” she admits. “When something is like not a good thing, the level of pain it causes is completely irrational and overblown, but it’s real.”

That sensitivity drives their obsessive attention to every detail. They don’t want their objects to have any feeling of compromise around them. No corners cut. No frustrating interactions. Just joy.

The Philosophy Made Physical

Walk through CW&T’s catalog and you’ll see this philosophy crystallized into objects you can hold.

Take their Pen Type-C. It solves a specific problem: how to always have a pen without it being annoying to carry. Its flat, wide profile is thin enough to clip to a wallet or notebook without adding bulk, yet substantial enough to feel natural in your hand—almost like a carpenter’s pencil. That’s the clever bit: most compact pens sacrifice comfort, becoming awkward little tubes that cramp your fingers.

CW&T machined this from grade 5 titanium with a glass bead blast finish, so it’s built to last years. The stainless steel clip is removable if you prefer it clipless (just needs a flathead screwdriver). And unlike typical space-saving pens with scratchy refills, this uses a quality cartridge that actually writes smoothly. It’s the kind of design that makes people ask about it.

Or consider Spicy, their spice grinder that breaks every rule of kitchen tool design. Most grinders optimize for capacity or grind settings or easy refilling. Spicy optimizes for the experience of grinding spices. It’s a small, dense cylinder of stainless steel with ceramic burrs that produces an almost meditative grinding action. You can’t grind a tablespoon of pepper at once. You have to engage with it, turn it. It’s deliberately slower.

“We never like to think of our products or the things that we make as like the best of this thing in a category,” Taylor says. “None of our stuff is something that you have to have. It’s mostly like these things just bring us joy, answer some curiosity, and hopefully maybe that can instill some curiosity or answer or start to get at some question or shift the way that you see the world in some slight way.”

The Cult of Prototyping

Perhaps the most revealing aspect of CW&T’s practice is their absolute rejection of digital renderings.

In an era of hyper-realistic 3D renders that can sell a product before it exists, CW&T refuses to use them internally. As Che-Wei has explained in interviews, they never produce renderings for themselves—they go straight to prototyping, and the thinking happens there.

The rationale is simple but profound: a rendering communicates a false idea.

They emphasize that the gap between a functional prototype and a manufacturable product is enormous and often underestimated by young designers. Che-Wei has described how there’s a whole chunk of work between having the idea and making it manufacturable that people often miss. Sometimes it’s a couple of prototypes, sometimes it’s literally hundreds. No shortcuts, unfortunately.

This insistence on physical iteration—on touching, using, living with objects—is central to their philosophy. Ideas don’t come from brainstorming sessions. They come from “living life,” from long walks, from quiet time in museums, from “removing stimulus” and letting ideas bubble up.

It’s the same lesson Che-Wei learned in that high school art room: unstructured play with raw materials reveals truths that planning never could.

The Cure for Feature Creep

CW&T won the Cooper Hewitt National Design Award for product design in 2022. They’ve built a devoted community on Reddit and Discord. They hold monthly virtual office hours where seven strangers can sign up to talk about projects, life, anything. They share their manufacturing contacts freely. Nothing is secret.

Che-Wei and Taylor have arrived at the same truth: creativity isn’t magic, it’s permission. Permission to take things apart. Permission to make things badly at first. Permission to design for yourself and trust that honesty will find its audience.

Stop looking for the gear that does everything. Start looking for the gear that does one thing so well, it makes you a little bit happier every morning.

That’s the CW&T promise. And it’s working.

CW&T’s complete collection—including Time Since Launch, the Solid State Watch, Pen Type-C, and Spicy—is available at cwandt.com. Each piece is designed and assembled by hand in their Brooklyn workshop.

Photography credits include: Bryson Malone, Shane Singh and Dean Liaw.

Carry Awards

Carry Awards Insights

Insights Liking

Liking Projects

Projects Interviews

Interviews