Carry 101

When a backpack finally slings over your shoulder, there's a lot that has gone into it. It's lived a whole life before it's found its way to you. Beginning as raw materials, then manufactured into components, and slowly put together, piece by piece, and shipped around the globe. It's a more complex process than you might think. And every step along the way has an impact.

So we've decided to track the whole thing – a complete life cycle of a backpack. In this piece, I’ll use an actual real-life product. The subject of this story is a backpack produced exclusively for players at the 2020 Australian Open.

Backpacks currently represent around 10% of all bags sold and this one’s fairly typical. It’s also a bag that I helped create, so it wasn’t hard getting a peek behind the curtain.

What makes up a backpack?

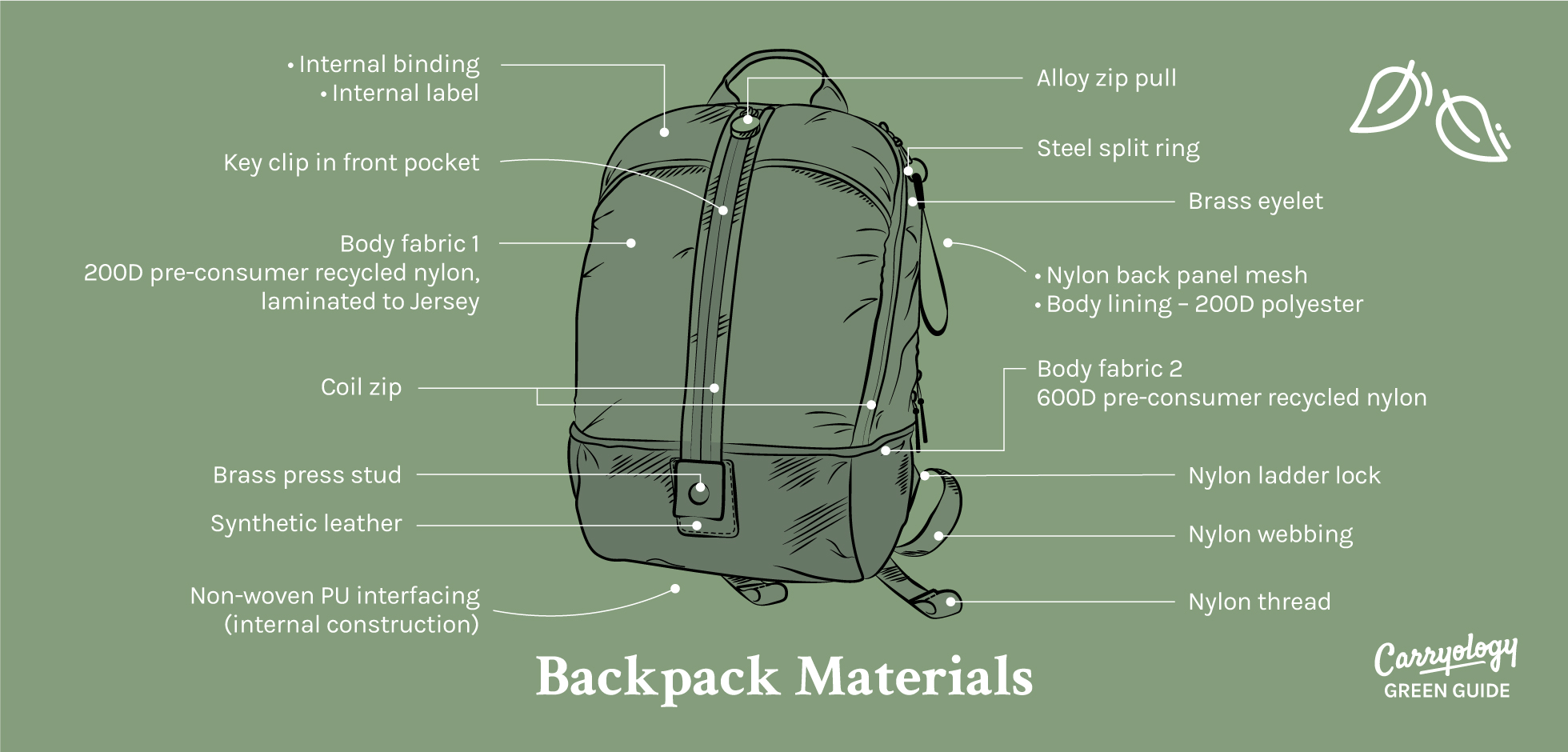

When trying to get your head around how a bag is made there are two issues that combine to create a headache. Firstly, most bags tend to be made from an inordinate number of different materials. Take a look around the room you’re in, I’d guess that most objects you see will consist of just a few parts. Bags, however, involve a number of materials disproportionate to their price. Looking at the bill of materials for our test pack I counted 23 in total, nine of which are just different fabrics.

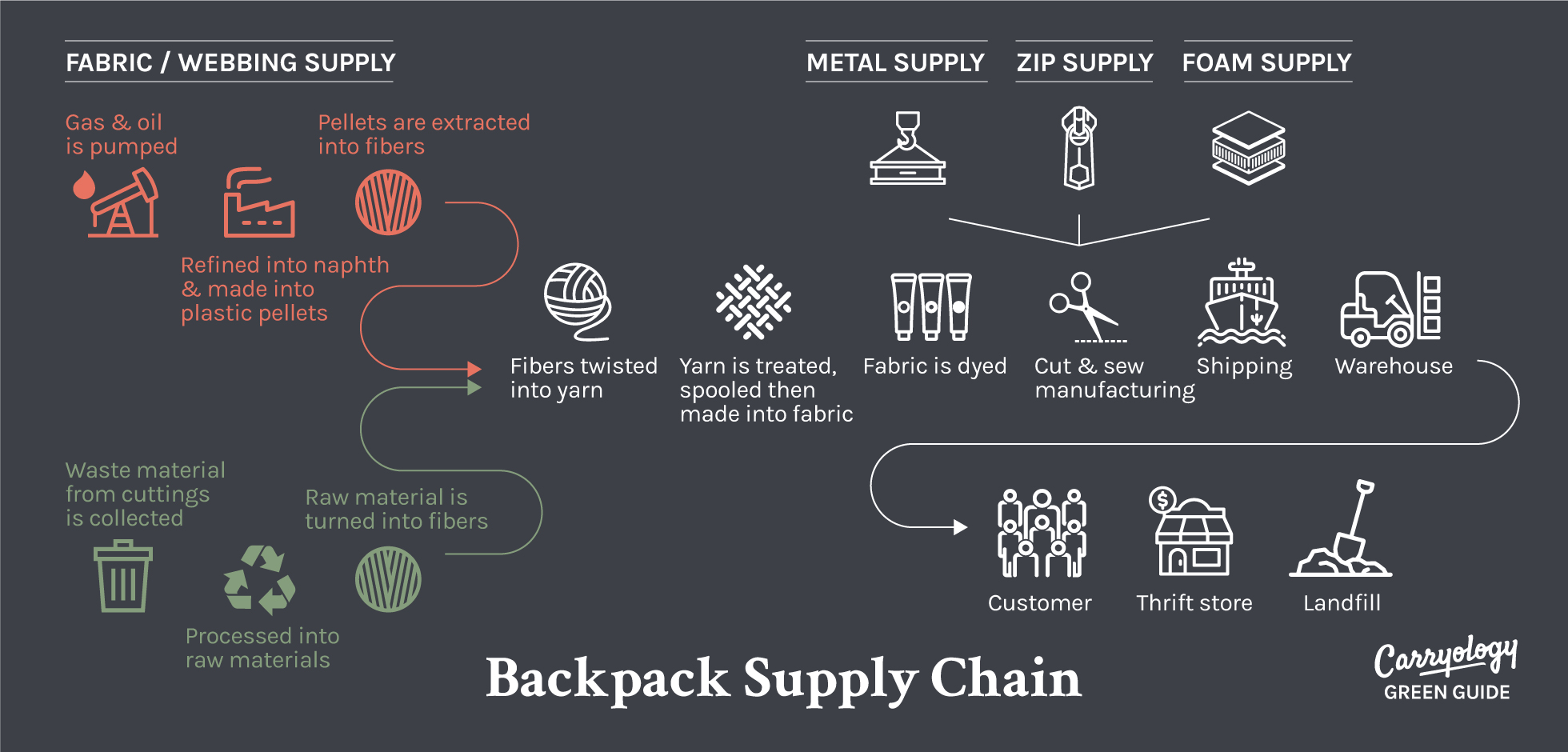

Secondly, there are an inordinate number of steps involved in producing textiles. For example, there are around ten separate steps involved in the supply chain to produce nylon fabric. So if making nylon is any guide, it took a possible 90 suppliers just to make the fabrics alone.

To make it easier to understand, let's break down the bill of materials by weight: 65% of the bag is made from three textiles, two of which come from recycled pre-consumer waste nylon. The other is a virgin polyester which started life as crude oil pumped from the ground in one of the oil-producing countries, for instance, the US or Saudi Arabia. After drilling the oil is refined, processed into plastic pellets and sold to the yarn producer in China.

From that stage the process for both virgin and recycled fabrics is similar, yarn is formed and then knitted or woven into a textile. The textiles are then dyed, given waterproofing treatments and in some cases laminated together.

Foam makes up another 15% of the bag. The three different foams used are all produced in China and all are oil-based. The remaining 20% is made up of a long list of small items like zips, hardware and trims. Of these only four elements aren’t derived from oil; that’s the zip sliders, press studs, eyelets and the keying which are made from a mix of metals.

Production and shipping for this long list of materials is a slow process, taking over three months. In contrast, once they arrived at the manufacturer in southern China it only took a few days to cut and sew the bags.

After the bags were stitched up and quality controlled, they were packed into cartons and loaded onto a shipping container which sailed around 5000 nautical miles to Melbourne Australia. In this case, distribution was super simple, but typically there would then be a domestic supply chain needed to get the bags into the hands of loving customers.

Typically after a few years together, maybe ten if we’re really lucky, the bag will be replaced. It might be passed on to be reused but eventually it’ll be broken beyond repair, at which point it’ll need to be disposed of.

What are the environmental impacts of producing a backpack?

Of all the side effects, inefficiencies and byproducts of the process described above, most sustainable brands and products address one or a handful of the following environmental impacts.

Resource depletion

First cab off the rank is resource depletion. In the case of our test bag around 90% originated from crude oil which is a finite resource. Despite the fact a good proportion of the bag used recycled nylon, that resource currently relies on the production of virgin nylon. Estimates are that if we continue the current rate of oil consumption we'll use all the available oil in the next 50 years.

Water

Water is another valuable resource which is impacted in various ways through the process. Both oil refinement and plastic processing consume water for cooling. Further down the chain, the textile formation causes both water pollution and eutrophication, which is the over-enrichment of water with nutrients and minerals. Of the world's available fresh water, around 20% is currently used by industry. As the global population grows, access to clean water is a growing concern.

Chemical

Fabric treatments and finishing processes such as dyeing, printing, laminating and waterproofing each have a unique reliance on chemicals. These chemicals can have severe impacts on both human and environmental health. It’s hard to summarise the chemical impacts of fabric production due to the wide array of chemicals and processes used. For example synthetic dyes may contain sulphur, acetic acid, enzymes, copper, arsenic, lead, cadmium, mercury, and nickel. In 2012 the World Bank estimated that fabric dyeing was responsible for up to 20% of global water pollution.

Electrical

From oil refining down to sewing, all of these processes rely on electricity. Currently, around 60% of China's electricity comes from coal and gas. This combination of factors has led to China's infamous air quality as well as its rank as the largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Fuel

Once the bags are on the water shipping becomes a major source of carbon emissions. The fuel used by ships is low grade and high polluting. In 2014 it was estimated that shipping accounted for 3% of global emissions, that’s more emissions than all of Brazil. Thankfully in our case, we were able to sea freight; air freight emissions are around thirty times greater again. Why are emissions a problem? Evidence shows that human-induced emissions are responsible for 100% of global warming since 1950.

Waste management

Waste management and recycling is a concern through the latter stages of the journey. Firstly at the manufacturer cutting waste is produced and rarely recycled. Packaging is then needed for transportation and at point of sale. But the greatest waste management challenge comes once a bag reaches its end. Due to the fact they’re sewn together there’s currently no practical solution to recycle a bag due to the wide mix of materials that are incredibly slow to separate. The best case at the moment is to repair bags; if that’s not possible then downcycling them is the next best option. Unfortunately due to this issue, most bags end up in landfill which squanders the possibility of reusing those valuable materials.

And whilst our bag isn’t made from natural fibers like cotton, wool or leather, these fibers have equally damaging impacts associated such as water use, impacts on ecosystems and animal rights issues.

The biggest issue

There’s not anything remarkable about the life cycle of the pack in our case study. The materials, processes and places involved are indicative of the majority of bags available today. The biggest issue is that it's a process that’s evolved with the single goal of cost efficiency, and in most cases, with no regard for the environment.

Today it’s the most competitive way to manufacture a product, which is why it’s also the most common. With no alternative sustainable supply chains easily available in the short term, for now the goal for brands is harm reduction. We have to find ways to improve mass manufacturing as it will remain the most common way bags are manufactured for the foreseeable future.

Which leads to the topic of the next instalment, where do we start with harm reduction and what's the solution?

Look out for Part 3 and 4 coming soon…

Part 3: What's the solution?

Part 4: What can I do?

Carry Awards

Carry Awards Insights

Insights Liking

Liking Projects

Projects Interviews

Interviews