The Life and Times of the Modern Tactical Backpack

We teamed up with Huckberry to dig deep into the history of the modern tactical backpack; a history filled with struggles, successes and groundbreaking carry innovation. Enjoy!

Humans love to lug. We’ve been doing it for millennia. The backpack is, in many ways, a primordial phenomenon. Yet what we’ve come to know as the modern tactical backpack – the sleek collection of utility designs that we know and love today – actually isn’t that old at all.

While the first wood-framed backpacks of the modern era sprung up across the world post-Gold Rush, military warfare throughout the 20th century took early prototypes down an experimental, and often haphazard, evolutionary path. Today’s ALICEs, MOLLEs and GORUCKs are the children of a formidable lineage, one full of misfires, trial and error, and one that kicked off not long after the American Civil War.

Merriam and the Hobo Blanket Stiffs

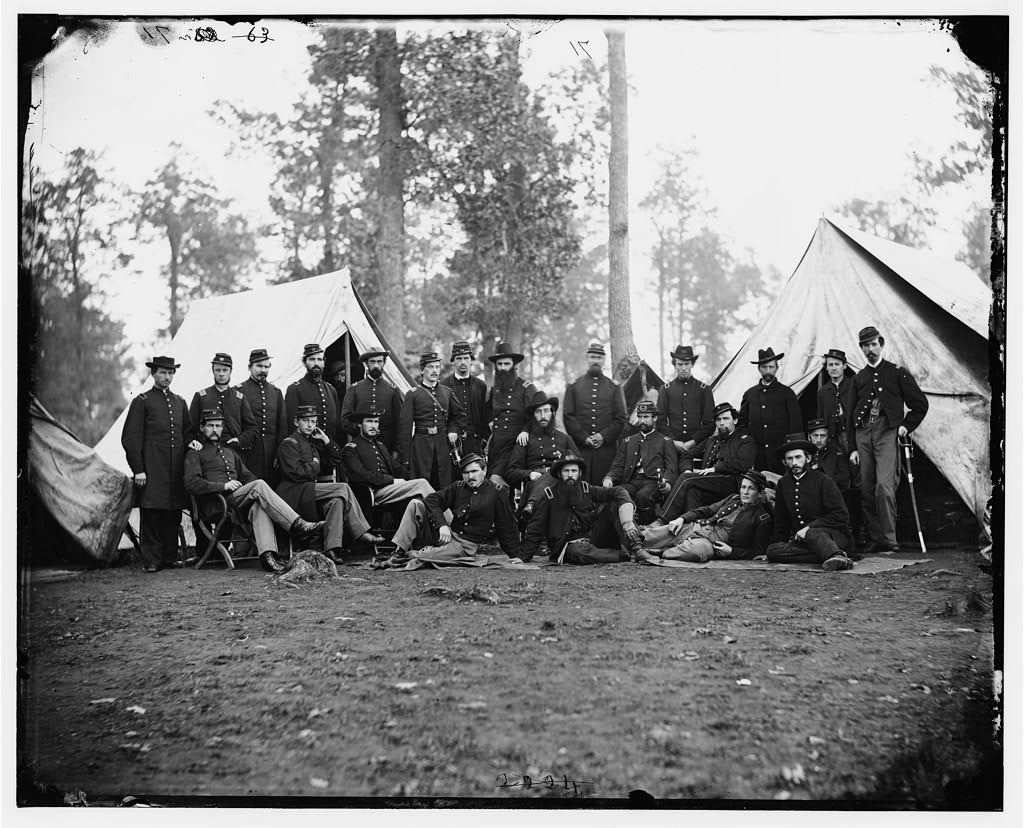

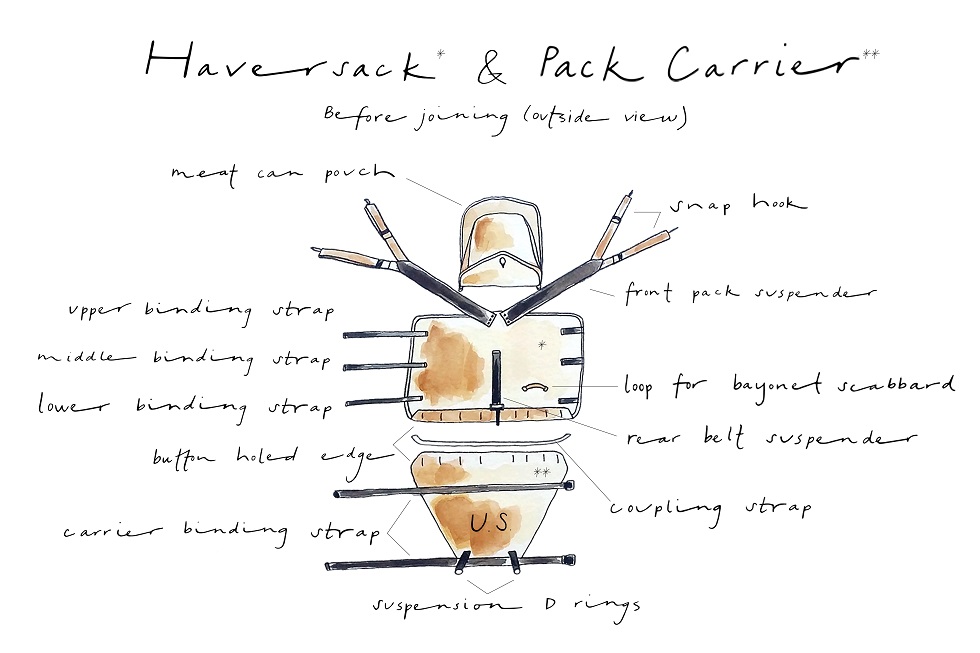

As far as carrying things on the field went, infantrymen across the world were resigned to a less than ideal kit in the 19th century: an unintegrated clutter of cartridge boxes, belts, canteens and bayonets. Each piece was designed in isolation, with scant consideration for how they’d interact when lugged in unison across the far reaches of the battlefield.

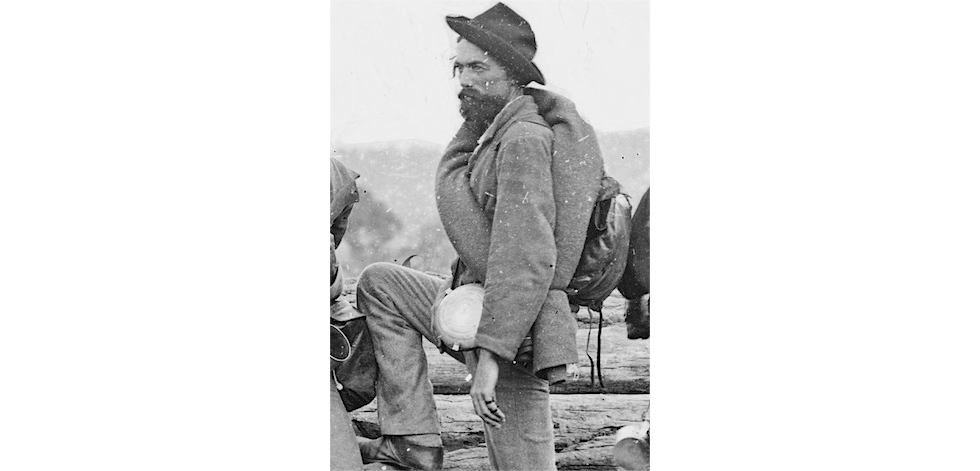

Though frameless khaki canvas haversacks and M-1853 Civil War knapsacks were on offer in the mid-century, American troops would often dump their standard issues and coddle gear in their blankets instead: rolled horseshoe-style, slung over shoulders to save on space, weight and discomfort. In the absence of a unified carry system, the blanket roll was a decent solution for New York Infantryman Charles Johnson Post: “It looks like a clumsy, amateur sausage lying out straight, but it is soft on the shoulder,” he wrote. However, “[it] made us look like a bunch of hobo blanket stiffs.”

"American troops would often dump their standard issues and coddle gear in their blankets instead: rolled horseshoe-style, slung over shoulders to save on space, weight and discomfort."

From 1870 on, the US army experimented with a number of different carry systems designed to corral the kit mess. One of the most afflicted, if not innovative, was that of US Colonel Henry Clay Merriam, commanding officer of the Seventh infantry.

Around 1874, the industrious Merriam got working on a new arrangement: the existing military knapsack and haversack would be fused into a single unit, with a rear hip-strap and exterior frame made of hickory to help transfer weight from the shoulders to the kidneys. Persistent, if not a little zealous, Merriam endured a decade of military red tape and flawed marketing before his sacks were finally trialed in a handful of regiments throughout the country. Acclaim was mixed: though the sack’s central section was allegedly quite good for hauling around a quart of whiskey, the cutting-edge ‘ergonomic’ frame led some to feel they were being yanked downhill with every stride. Dubbed ‘murdering sack’ by those less forgiving, Merriam’s design proved cumbersome, difficult to clean, and tough to access rations in. Depending on whom you asked, the latter gripe wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. In the words of Captain J. Ayers, ordnance officer for the Department of the Platte: “…it will prevent the wasting of supplies by inexperienced soldiers in constant nibbling.”

"Though the sack’s central section was allegedly quite good for hauling around a quart of whiskey, the cutting-edge ‘ergonomic’ frame led some to feel they were being yanked downhill with every stride."

Nonetheless, soldiers – both steel-stomached veterans and slipshod nibblers – got the last say. Dumping Merriam’s pack like so many others, they backed the tried and true: standard issue haversacks – so too the hobo blanket – for now at least, sufficed.

Nelson and the M-series

In 1909 the military commissioned a fresh standard issue to unite the necessities: the infamous M-1910. Particularly heinous on the shoulders, the M-1910 was a case of hopeful thinking rather than musculoskeletal redemption. The detachable waist strap was a welcome addition, but it did little to buffer the soldier’s load, functioning merely as a rung for more gear, such as a canteen and first aid kit. Numb arms were a common gripe. Because field rations and essentials were wrapped together in a single unit, you had to unfurl the whole bundle to retrieve anything; less than ideal in the midst of grisly battle. Accompanied by a four-page instruction manual, the maligned 70+ pound unit somehow remained in the mix until WWII. It can be said with conviction that the designers of this pack were probably not beset with the displeasure of having to ever wear it in practice themselves.

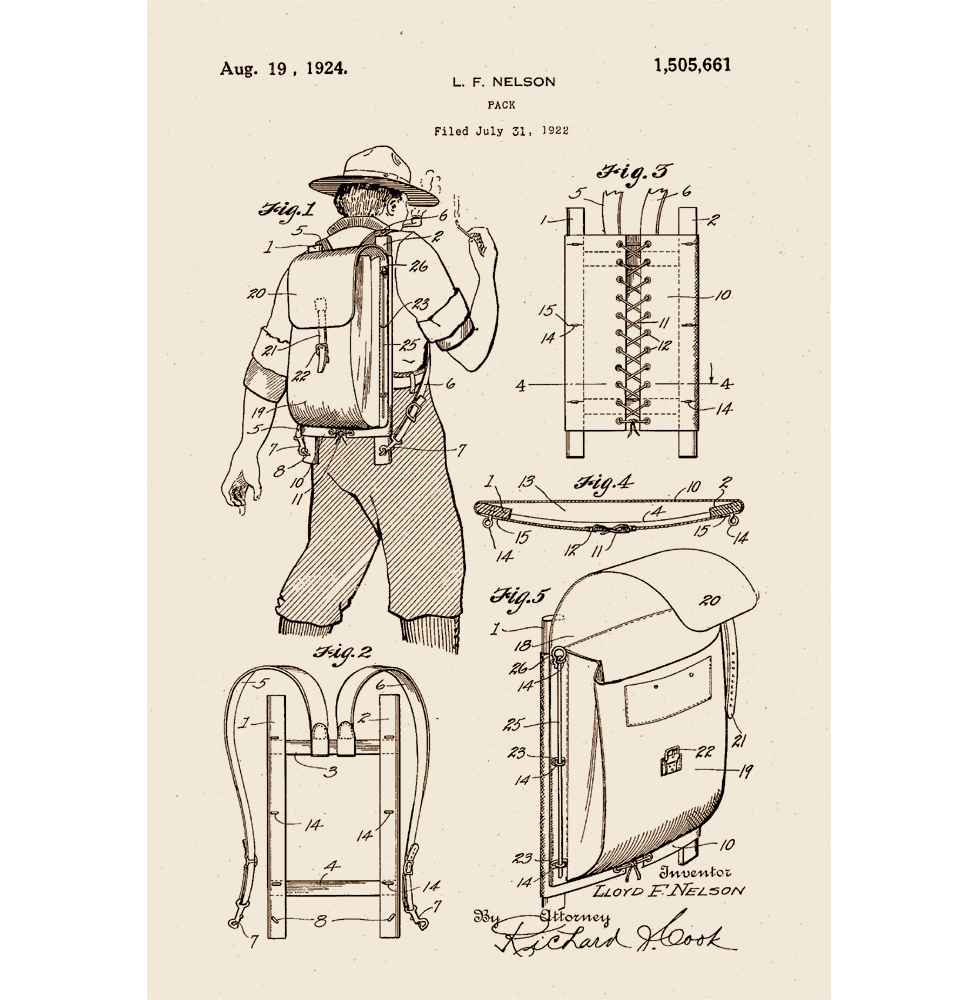

In the meantime, a civilian named Lloyd Nelson had been hiking around Alaska with a pack made of seal skins and sticks that he’d borrowed from a local indigenous tribe. Less than cozy for long hauls, Nelson craved something a little smoother on the vertebrae, and figured others might too. Building on the locals’ design, he devised an impressive external frame system: a wooden board with a canvas back panel, cross slats and detachable packsack. In 1922, the ‘Trapper Nelson Indian Pack Board’ was officially submitted to the U.S patents office. Yukon Gold Rushers were particularly enamored with it.

Regrettably, it was still pretty much hell on the shoulders, and though a trailblazing feat – considered by many to be the first external frame backpack ever seen – design-wise, it wasn’t too far off the ‘Sekk Med Meis’ frames devised by the Norwegians back in the 1880s (which, of course, Nelson would have had no idea about). Whatever came first elsewhere, Nelson’s Alaskan packboard is regarded by many as ‘where it all began’ for modern backpacking, and a vital link in military design thinking. That aside, the often under-appreciated inventions of the North American Indigenous cultures – Alaskan Inuits certainly, with regard to Nelson, but also tribes of the Seneca and Obijiwa nations – ought to be considered a crucial influence at this point in the carry evolution.

"In 1922, the ‘Trapper Nelson Indian Pack Board’ was officially submitted to the U.S patents office. Yukon Gold Rushers were particularly enamored with it."

Back on the Western battlefield, WWII raging in Europe, a newfangled model, the M-1928, finally superseded the ungainly M-1910. With little difference between the two, there wasn’t much for troops to celebrate. Thankfully, the succeeding M-1941, with its load-distributing integrated suspenders, was a step in the right direction: a two-section offering, with rations, poncho and clothes in the upper chamber, and shoes and utilities in a lower knapsack. Fashioned rather impressively over a matter of days, the khaki M-1941 held its own right through the Korean War, metamorphosing olive green during the early days of Vietnam, known simply as ‘Field Pack, Canvas, Combat.’

ALICE and the Rise of the Keltys

Thanks to an abundant supply of durable material resources, and the appearance of key inventions such as zippers and nylon, the end of WWII marked a new generation of backpack design in America.

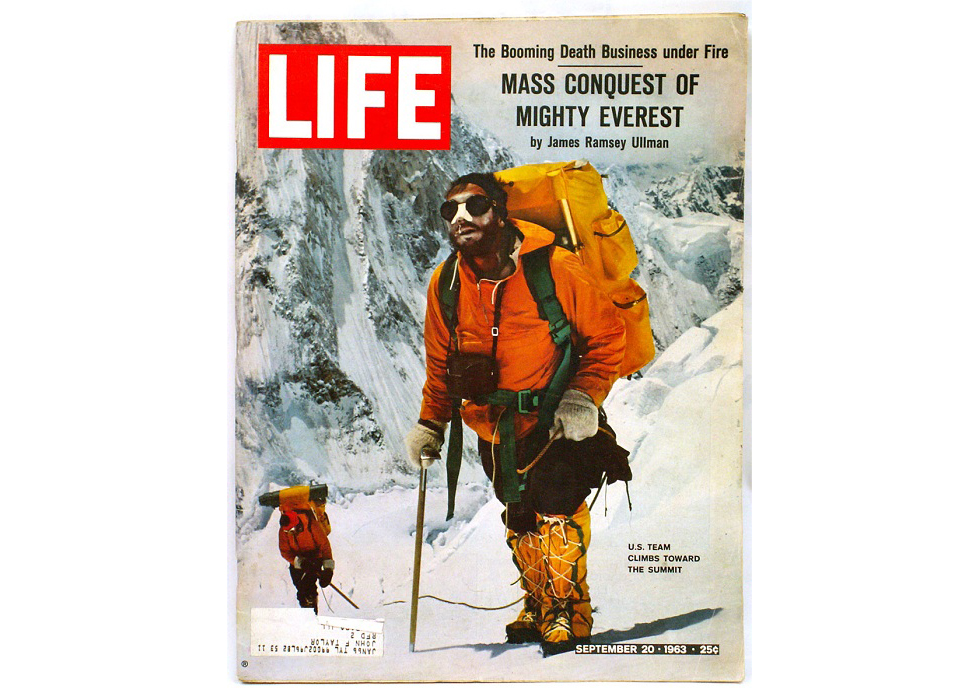

Confounded by the weight of existing military-style packs, hiking buffs Nena and Asher ‘Dick’ Kelty sought a solution to the punishing realities of recreational trekking. In their Californian garage, the Keltys set about handcrafting their own packs, employing a weight distribution system made of lightweight aluminum tubing. In 1952, they sold 29 units at $24 each; 90 the following year; 220 the next. In 1963, their packs were lugged exclusively on the first American ascent of Mt. Everest. While the addition of a proper load-bearing hip strap was added afterwards (finally validating Merriam’s 19th century inclinations), the Keltys’ initial frame concept – born of ingenuity and personal investment – signaled a paradigm shift in the carry world. Backpacks were about to get better. A lot better.

As we know, the ‘60s was a busy time, and warfare, against the hopes of Yoko, John, and the rest of the civilized world, was anything but over. So too, the fruition of state-of-the-art military carry, and an unhealthy love of the acronym.

An official 1962 defense paper, A Study To Reduce The Load Of The Infantry Combat Soldier catalyzed the LINCLOE system (Lightweight Individual Clothing And Equipment). Cotton canvas, nickel and brass of yesterday’s models were traded for lightweight nylon and plastic. To withstand the intense tropics of the Pacific Rim, the MLCE (Modernized Load-Carrying Equipment) was devised, morphing in 1973 into the robust ALICE (All-Purpose Lightweight Individual Carrying Equipment). The latter proved versatile, rugged and moisture resistant, and would play a key role in the military mix right up until the turn of the millennium.

"Cotton canvas, nickel and brass of yesterday’s models were traded for lightweight nylon and plastic."

In 1997, the military birthed MOLLE: pronounced ‘Molly’ (not mole), the new-generation system – easily ID’d by the crosshatched (and now ubiquitous) PALS webbing – trumped ALICE with an impressive range of locking pouches, a quick-release tactical assault panel over the chest, and an inbuilt hydration bladder. Not to be completely outdone, MOLLE’s fragile zippers and external plastic frame still cause many to champion ALICE as the superior prototype.

In the conflict of recent years, troops have embraced an even more progressive arrangement, through the advent of ILBE, or Improved Load Bearing Equipment. Crafted of robust denier Cordura with military pattern camouflage, the ILBE pack – son of MOLLE, grandson of ALICE – is the current head of the Family of Improved Load Bearing Equipment (FILBE).

"The Keltys’ initial frame concept – born of ingenuity and personal investment – signaled a paradigm shift in the carry world. Backpacks were about to get better. A lot better."

The influence of all this on everyday carry can’t be understated. Features like load-bearing back panels are staples in today’s tactical kits; MOLLE webbing is used on GORUCK, Heimplanet, and more or less any commercial pack brand trying to push the 'tacti-cool' edge; hydration bladders built into GORUCKs today give everybody the opportunity to ruck and suck down a little H2o while a bunch of cadres yell in their faces; to say nothing of cutting-edge adjustable sizing frames like Mystery Ranch’s Futura Yoke. Functional boons aside, all these features are just as much there to make a good-looking bag come off even more badass than it already is.

Here’s the skinny: modern military packs have become accessible to everyone, and they are everywhere. Design nous won’t let up – as the family tree sprouts, the search continues for the perfect pack, just as well as the next generation of exciting military acronyms. There’s no telling what the future holds – newer, fresher, more lightweight materials, perhaps some sort of load-bearing human-cyborg fusion, or indeed, cadres of robotic drones who need not the material comforts, or weight, of bygone human counterparts. One thing’s certain: short of some sort of dystopian material scarcity on a colossal scale, the return of the hobo blanket remains an outside chance at best, with the shoulder-destroying yesteryear of backpack carry, and the lofty visions of Merriam, Nelson, et al., all but distant, slapdash memories – ones that we’d all be far less unencumbered without.

Illustrations by Nicole Varvitsiotes.

Carry Awards

Carry Awards Insights

Insights Liking

Liking Projects

Projects Interviews

Interviews